Your child has just had their tonsils removed. The procedure went smoothly and as they are slowly waking up in post-op, you’re meeting with the surgeon and going over the recovery plan. The doctor prescribes three pain-relieving medications: ibuprofen, acetaminophen and oxycodone.

That last one sets off alarms in your head. Isn’t oxycodone an opioid? Aren’t those dangerous? Addictive? Even fatal? It seems every day there is some shocking news report on the current epidemic in the United States. You certainly don’t want that to happen to your child.

If you have any questions or concerns about your child’s pain management, don’t hesitate to talk to your child’s doctor. An informed population is the best line of defense. The daily news reports can be scary, but the truth is there are many misconceptions about these important pain relieving drugs.

1

“Many parents think if you use opioids for even a short period of time, you will get addicted. That is just not true,” said Steven Weisman, MD, medical director, Jane B. Pettit Pain and Headache Center at Children's Wisconsin. “I tell families all the time that the current epidemic is unrelated to appropriate medical use of opioids in children.”

What are opioids?

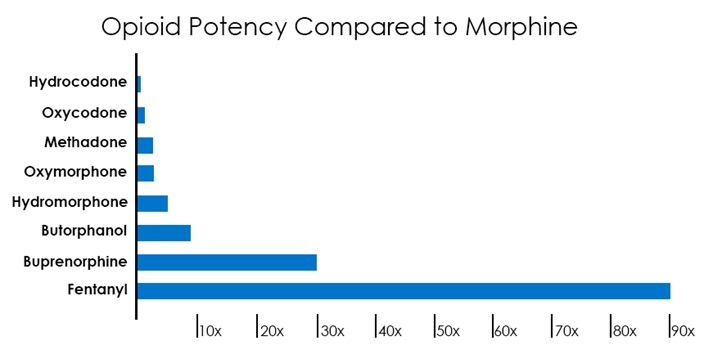

Opioids are pain relieving drugs that bind to receptors on nerve cells and block pain signals. Morphine is a natural form that comes from the poppy plant. Drugs such as hydrocodone, oxycodone, codeine and fentanyl are man-made and much more powerful.

Opioids are pain relieving drugs that bind to receptors on nerve cells and block pain signals. Morphine is a natural form that comes from the poppy plant. Drugs such as hydrocodone, oxycodone, codeine and fentanyl are man-made and much more powerful.

“People hear how strong fentanyl is and it scares them. But really it is all about appropriate dosages,” said Dr. Weisman. “That’s where our pediatric expertise is important. If you know how to use these drugs and how to dose them then one is as safe as the next.”

Why do some people get addicted?

When a person takes opioids, the body reacts by shutting off the endorphin system, which is your body’s natural pain relieving system. If that person abruptly stops using the opioids, their body isn’t given the proper time to readjust and start producing endorphins again. This can cause withdrawal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, severe agitation) and that can lead to your body craving the opioids to make it stop. That’s the physical dependence of addiction.

“Often, it’s not the drug that’s the problem, it’s how it’s managed,” said Dr. Weisman. “The weaning process is just as important as the actual treatment phase.”

Stopping the use of opioids gradually allows the endorphin system time to start up again, preventing withdrawal symptoms.

Of course, everybody is different. In general, if a person is on regular, daily doses of opioids for five to 10 days, they are considered to be at risk to develop some physical dependence. On the other hand, someone recovering from surgery or an injury could be on a dose here and a dose there for many weeks without developing physical dependence.

“It depends on the amount of opioids and it depends on genetic factors that vary from person to person,” said Dr. Weisman. “On average, that one week timeframe is an important point in our minds. It’s the regular use, bathing your brain in opioids continuously that leads to the development of dependence.”

How to reduce opioids in the community

Although there are many opioids in the community, Dr. Weisman stressed that the vast majority of the current opioid epidemic is not taking place in the pediatric population. Most of the abuse in pediatrics is in teens and young adults who are experimenting with drugs and stealing opioids from family or friends. Dr. Weisman recommends that all opioids at home be kept in a safe and secure location and parents should carefully track what’s been given and how much remains. If you have a large amounts of unused and unwanted opioids, look for a proper prescription drug drop-off location in your area.

Although there are many opioids in the community, Dr. Weisman stressed that the vast majority of the current opioid epidemic is not taking place in the pediatric population. Most of the abuse in pediatrics is in teens and young adults who are experimenting with drugs and stealing opioids from family or friends. Dr. Weisman recommends that all opioids at home be kept in a safe and secure location and parents should carefully track what’s been given and how much remains. If you have a large amounts of unused and unwanted opioids, look for a proper prescription drug drop-off location in your area.

2

One way Children’s Wisconsin is leading the effort to reduce the abundance of opioids is with electronic prescriptions. In the past, a patient needed a paper prescription to get opioids from a pharmacy. And if they ran out and needed more, they had to come back to the hospital and get another paper prescription.

“If a family lives three hours away, it’s unreasonable to expect them to drive all that way just to get a new paper prescription,” said Dr. Weisman. “So doctors would often give patients an ‘insurance prescription,’ maybe 50 percent more than they thought they would need just to help them not be inconvenienced when they’re nursing a sick child. That has contributed to the availability of unused opioids in the community.”

But now, through electronic health records, Children’s Wisconsin doctors can securely send prescriptions — even for opioids, which are controlled substances — directly to a patient’s pharmacy. That allows doctors to prescribe smaller initial amounts. Then, if several days later, the child is having a harder recovery and is still in pain, the doctor can electronically submit another small prescription to carry them through the rest of their recovery. Smaller prescriptions means less unused opioids in the community.

Alternative pain relief approaches

For years, Children’s Wisconsin has deliberately used a multi-modal approach to pain relief, rather than relying solely on opioids for treating pain. That means using multiple different types of medications and treatments — opioids and non-opioids — to treat pain.

Let’s go back to the kid who just had his tonsils removed. Every year, Children’s Wisconsin performs hundreds of tonsillectomies. It’s a common surgery with a very painful recovery that can last up to a week. Those kids are sent home with prescriptions for ibuprofen, acetaminophen and a small dose of oxycodone as a backup.

“That multi-modal approach is not because of fear of addiction but rather because opioids can have significant side-effects. Opioids can cause nausea, vomiting, itching and constipation. That’s the last thing you need when recovering from surgery,” said Dr. Weisman. “In addition, research has demonstrated that for many children ibuprofen and acetaminophen are sufficient for pain control. Limiting use of opioids is just good medicine and it also aligns with national initiatives to help curb the opioid epidemic.”

Children’s Wisconsin doctors also use something called nerve blocks, where local anesthetics are injected around nerves to numb them. For kids who have reconstructive knee surgery, for example, doctors will leave a small catheter near one of the nerves in the groin. They are then sent home with a small pump that delivers pain-relieving medicine to that nerve for up to three days. Those patients can often recover without any opioids.

“We’re doing all these things not because of the opioid epidemic, but rather to provide the best care to kids,” said Dr. Weisman. “A child having an operation should not be denied good pain relief with an opioid because of this fear of addiction. If their medicines are managed properly and they receive the right care, they will not get addicted.”