Dalton is one in a million, but you wouldn’t be able to tell that just by looking at him.

In most regards, Dalton is a typical tween who loves video games, playing hockey, sleeping over at friends’ houses, and eating sub sandwiches. But in November 2019, Dalton’s mom, Mara, asked him to try on a new shirt. When Dalton changed out of his usual baggy sweatshirt, Mara was shocked by what she saw.

“Dalton’s face was still chubby — it was not gaunt,” said Mara. “But when I saw him without a shirt, I knew something was not right.”

Dalton’s torso was shockingly thin, his skin clinging to his visible ribs and spine.

“We started talking and Dalton admitted he was having episodes where food would get stuck in his throat 3 to 4 times per week,” said Mara. “When he would have an episode, he wouldn’t be able to eat or drink for the rest of the day.”

Dalton had noticed his difficulty swallowing a few months prior to telling his mom about it, but had been embarrassed to say anything. With no prior medical conditions, Mara quickly made an appointment with their family doctor who then referred them to a local gastroenterology (GI) doctor in Marshfield who suspected a condition called achalasia.

Achalasia is a rare swallowing disorder that affects about 1 in every 100,000 adults in the United States and only 1 in 500,000 children. For patients with achalasia, the nerve cells in their esophagus (the tube that carries food from the mouth to the stomach) deteriorate for reasons that are not well understood. This loss of nerve cells causes two main problems in the esophagus that disrupt swallowing.

The first issue is that the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) does not function correctly. The LES is a muscular ring that encloses the lower portion of the esophagus. Normally, when we swallow food, the LES relaxes to allow the swallowed food into the stomach. Once the food is in the stomach, the LES muscle contracts, squeezing the esophagus closed again to prevent what’s in your stomach from coming back up your throat (reflux).

The second issue is that the muscles lining the esophagus do not contract in a coordinated fashion, so swallowed food or liquids are not moved properly down the esophagus and into the stomach.

In achalasia, the LES continues to contract — essentially it stays in a “closed” position — so when food or liquids reach the bottom of the esophagus, they cannot properly pass into the stomach and either stay stuck in the esophagus or slowly drip through.

While Dalton’s local GI doctor suspected achalasia, the tests he performed were not conclusive for the condition.

This left Mara to examine whether Dalton was under stress or suffering from a psychological condition, while also adjusting Dalton’s food so he wouldn’t continue to lose weight.

“I was having Dalton cut his food into miniscule bites — smaller than baby-sized bites — and having him eat while standing up with his arms above his head to try to use gravity to move food down his throat,” said Mara.

After checking with Dalton’s school counselor who assured Mara he didn’t see any psychological causes for the episodes, she began researching achalasia in earnest while also keeping a food diary of everything Dalton ate, how much and when.

“We were both miserable,” said Mara. “I was so stressed trying to figure out different ways to get food into Dalton. Knowing he was starving and hearing him say, ‘I’m so hungry,’ was heartbreaking. I was on the computer every single day looking up achalasia and other potential causes. I probably drove people crazy talking about it.”

An exceedingly rare condition

Meanwhile, the episodes slowly started increasing in frequency. Dalton eventually stopped eating lunch at school because he felt embarrassed that it took him so long to eat, and also because he didn’t want food to get stuck at school.

Meanwhile, the episodes slowly started increasing in frequency. Dalton eventually stopped eating lunch at school because he felt embarrassed that it took him so long to eat, and also because he didn’t want food to get stuck at school.

“I could feel the food in my throat,” said Dalton. “I would try to swallow it and drink some water, but it would just never go down. Eventually I would go into the bathroom and cough it back up.”

Dalton only confided in two of his closest friends about what he was experiencing. If he had an episode in front of his hockey teammates or around other people, he tried to nonchalantly excuse himself to go to the bathroom.

While Dalton found workarounds for his condition in public, he and Mara definitely knew it was not normal. In spring 2020, Dalton’s GI doctor performed an additional test, a swallow study, that demonstrated where in Dalton’s esophagus things were getting stuck. Knowing that Dalton would need specialized testing to make a definitive diagnosis, Dalton’s GI doctor referred him to Karlo Kovacic, MD, a pediatric gastroenterology specialist with the Children's Wisconsin Gastroenterology, Liver, and Nutrition Program, for a high resolution esophageal manometry study. Esophageal manometry measures pressure and fluid movement in the esophagus and LES. Children’s Wisconsin is one of the only pediatric facilities in the Midwest to offer this procedure and have the capability to interpret its results.

Following the manometry study, Dr. Kovacic diagnosed Dalton with type 3 achalasia, an exceedingly rare condition for a child. Type 3 achalasia is the most severe and is characterized by spasmic squeezing of the esophagus and LES.

“The spasms Dalton had were a huge discomfort, but he would always downplay them,” said Dr. Kovacic, who is also a fourth year fellow and instructor of pediatric gastroenterology at the Medical College of Wisconsin. “It’s like having one of those really bad calf cramps that don’t want to let up. You can tell Dalton had been living with this for a long time because it became part of his norm. I told his mom, ‘You have a tough kid.’”

A novel surgical procedure

According to Dr. Kovacic, there are almost no reports of type 3 achalasia in kids.

According to Dr. Kovacic, there are almost no reports of type 3 achalasia in kids.

“It makes sense why Dalton’s initial test results were not clear cut because he didn’t present as type 1 or 2 achalasia, which while still rare, are more common,” said Dr. Kovacic.

For Mara, these are not the odds any parent hopes for.

“It’s rare to have achalasia. It’s rare to be an adult with type 3 achalasia. And it’s even more rare for a kid to have type 3 achalasia,” said Mara. “I didn’t want my kid to be one in a million!”

There is no cure for achalasia that will restore normal function to the esophagus and LES. Treatments involve relaxing the LES muscle so that food can empty from the esophagus into the stomach. Frequently, this is achieved through a surgical procedure where the muscle fibers of the LES are cut so the valve at the bottom of the esophagus relaxes. The most common surgical technique is called the Heller Myotomy, which is performed laparoscopically through small abdominal incisions. Dr. Kovacic referred Dalton to Dave Lal, MD, a general pediatric surgeon at Children’s Wisconsin with experience in surgical treatment of achalasia.

In reviewing Dalton’s rare case with Dr. Kovacic, Dr. Lal was concerned that a traditional Heller Myotomy may not be enough to significantly reduce or eliminate Dalton’s symptoms. Dr. Lal, who is also a professor of pediatric surgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin, was interested in pursuing a relatively new procedure called Peroral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM). POEM is an endoscopic technique that cuts the muscle fibers without any external incisions. The entire procedure is done through the mouth with a long, flexible tube called an endoscope. Being less invasive, there is no external scars, substantially less pain and a shorter recovery period.

More importantly for Dalton’s case, the POEM procedure is more effective in reducing symptoms for people with type 3 achalasia than the traditional Heller Myotomy. However, POEM is a challenging endoscopic surgical procedure that requires advanced skills and is only offered in a limited number of hospitals in the United States.

Dr. Lal thought Dalton would be an excellent candidate for a POEM procedure, but no one at Children’s Wisconsin had ever performed one before. Dr. Lal reached out to his colleague Andrew Kastenmeier, MD, a general surgeon at Froedtert Hospital and an associate professor of general surgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin, who had been performing the POEM procedure in adults at Froedtert since 2016.

“Dr. Kastenmeier trained with one of the first doctors in the United States to perform the POEM in adults,” said Dr. Lal. “Since achalasia is a rare condition, especially in children, we are just starting to see the procedure being used with kids. We knew Dr. Kastenmeier had the experience and technical expertise in the procedure and we asked if he would be willing to partner with us to offer the procedure to Dalton and he graciously agreed.”

Mara and Dalton had a consultation with Dr. Lal and Dr. Kastenmeier where the doctors explained both surgical procedures in detail. Mara, having done extensive research on her own, felt more comfortable with the Heller Myotomy going into the meeting.

“They were with us for 60 to 90 minutes and explained everything and answered all of our questions. I thought that was pretty phenomenal,” said Mara. “Dr. Kastenmeier was able to explain exactly how the POEM would work.”

Ultimately, the doctors told Mara and Dalton it was their decision.

“I wished they would have told me what to do,” said Mara. “I did ask them what they would do if it was their kid. Dr. Lal said he would choose the POEM because it was less invasive and Dr. Kastenmeier said he would choose the POEM because it produced better results for patients with type 3 achalasia.”

Taking everything into consideration, Mara opted for the POEM procedure because she hoped it would be more effective. “I didn’t want Dalton to undergo a Heller, have it not work, and then have to do the POEM anyway.”

Even though Mara and Dalton felt comfortable with the doctors and Mara was confident in her decision, it was still nerve-wracking.

"We knew Dalton was going to be the first child at Children’s Wisconsin to have the POEM and nobody wants to be the first,” Mara said. “We talked about the procedure at home every day.”

Sweet relief: To eat again

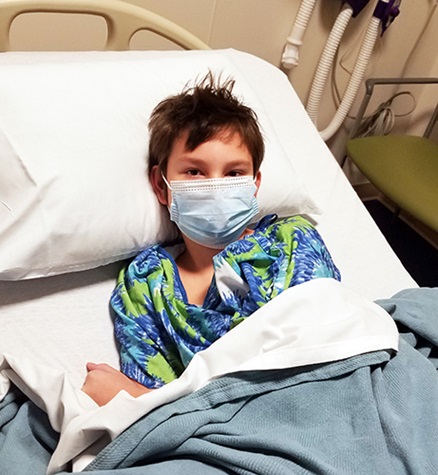

Despite their nerves, Mara remembers smiling on the day of surgery and thinking, “This is happening.” Dalton underwent the POEM procedure on October 21, 2020 and everything went beautifully.

Despite their nerves, Mara remembers smiling on the day of surgery and thinking, “This is happening.” Dalton underwent the POEM procedure on October 21, 2020 and everything went beautifully.

“Our experience was phenomenal,” said Mara. “I had all the trust in the world in Dr. Lal and Dr. Kastenmeier.”

Performing the first POEM procedure on a child in Wisconsin is a milestone achievement. Dr. Kastenmeier explains the procedure has only been done on adults for about 10 years.

“The POEM procedure occupies this zone between gastroenterology and surgery and there aren’t many people who fit in that zone, therefore there aren’t many training opportunities to learn the procedure,” said Dr. Kastenmeier. “In addition, the equipment that’s required is not commonly used in the operating room. It’s usually in the GI lab, so having equipment in the right place is important.”

Dr. Lal added that having the ability to diagnose achalasia in the Children’s Wisconsin GI lab is also extremely valuable.

“Many pediatric hospitals do not have the GI program to support evaluation of this disease,” said Dr. Lal. “The GI doctors don’t sit in on the surgery, but they are an important part of diagnosis and treatment. Our consultations with Dr. Kovacic informed our surgical decisions.”

One of Mara’s greatest takeaways about her experience at Children’s Wisconsin was how all of the doctors went out of their way to put them at ease and make sure she and Dalton had all the information they needed.

“The doctors were so friendly and they made us feel welcomed with open arms,” said Mara. “They were very direct and described things in a combination of doctor’s terms and layman’s terms. They didn’t care how many questions I asked. Even when I asked the same question four different ways, they would just re-answer my question. They took it all in stride. I felt completely confident that they were always working in Dalton’s best interest.”

Dalton appreciated that the doctors also spoke to him directly, not just to his mom, making him feel like he was an important part of the process.

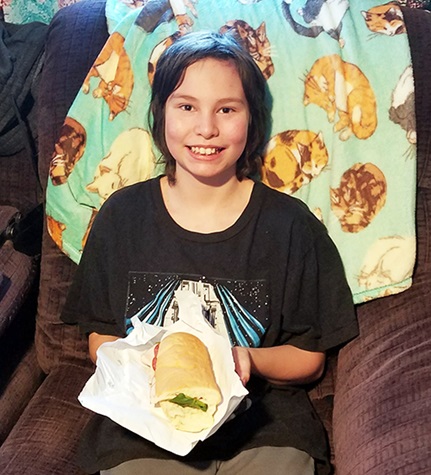

Since the procedure, Dalton has only had three episodes of food getting stuck, but even in those instances, the food eventually went down and nothing came back up. He’s now able to eat things that were previously too difficult, like subs or BLTs. And, he isn’t worried about eating at school or in front of his hockey friends anymore.

Dalton will continue to receive follow-up care with Dr. Kovacic to monitor for acid reflux.

“Achalasia is a horrific condition for kids and their parents,” said Dr. Lal. “You take a kid who is one day totally normal and then suddenly losing weight and always hungry. It affects their quality of life because kids feel embarrassed to go on sleepovers or to a friend’s house. This procedure makes an instant difference and families are so grateful.”

For Dalton, who is now 12 years old, the most obvious and dramatic result after the surgery is simple: “I can eat again and that makes me feel happy.”