Headaches can mean lots of things — stress from school, too much time in the sun, not enough water, a sinus or ear infection. But for 11-year-old Arie Stoker, they meant something far more serious.

It was early one evening in late April of 2022. Arie was at home when suddenly her head flooded with a deep and unrelenting pain. Intense nausea soon followed and Arie started vomiting uncontrollably. Her mom, Lacey, immediately called 911.

“I got the first call around 8 p.m. that Arie was throwing up and she was taking her to a hospital in West Bend,” said Tony, Arie’s dad. “The second time she called me, there was an ambulance on its way to take her to Children’s Wisconsin.”

A CT scan done at the initial hospital revealed a bleed pattern in Arie’s brain that is commonly seen with a ruptured aneurysm. At Children’s Wisconsin, some additional tests and scans quickly confirmed the suspicion. Due to the complicated nature of Arie’s aneurysm, the following day, Hirad Hedayat, MD, a neurosurgeon at the Children’s Wisconsin Neurosciences Center, took over her case.

A rare and complex defect

An aneurysm is a bubble in or on an artery or vein in the brain that creates pressure on surrounding tissue or nerves. If it ruptures, blood will pour into the surrounding tissue, possibly causing brain damage or, in worse cases, death. Aneurysms most typically occur in adults over 65 years old with a history of smoking, high blood pressure or high cholesterol. In children, they’re quite rare. And their cause is often unknown.

An aneurysm is a bubble in or on an artery or vein in the brain that creates pressure on surrounding tissue or nerves. If it ruptures, blood will pour into the surrounding tissue, possibly causing brain damage or, in worse cases, death. Aneurysms most typically occur in adults over 65 years old with a history of smoking, high blood pressure or high cholesterol. In children, they’re quite rare. And their cause is often unknown.

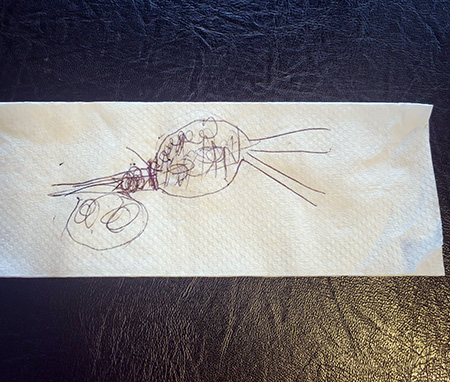

“It’s scary to hear something’s wrong with your kid’s brain,” said Tony. “I met them at Children’s Wisconsin right away. They told us that it was a very rare type of aneurysm. The doctor drew it on a napkin to explain it to us.”

“Arie had a complex aneurysm,” said Dr. Hedayat. “Generally, aneurysms are located on the side of the head and you can just go in and close it off. But hers actually involved the main blood vessel going to the back of the brain, which is the area that processes vision called the occipital lobe.”

The most common treatment for an aneurysm is a procedure called coil embolization. In this minimally invasive procedure, a surgeon will make a small incision in the patient’s groin, insert a thin tube called a catheter into an artery and feed it up to the brain. Tiny metal coils are then placed inside the aneurysm, causing it to shut down and no longer have a risk of rupturing again. Complicating matters, however, was Arie’s aneurysm involved the main artery itself along with the branches coming from it, not like the more common aneurysms located on the side of a blood vessel.

“If Arie’s aneurysm were coiled, you basically give her a stroke to the part of the brain those blood vessels support,” said Dr. Hedayat. “For Arie, with her aneurysm where it was, cutting off the blood flow to the part of the brain that controls vision, losing her sight on the left side would have been a major risk.”

With her type of aneurysm, if you coil it off and the blood vessel involved, the hope is other blood vessels in the region will take over blood flow. “She’s young and the blood vessels can do that”, said Dr. Hedayat, “but that's a gamble.”

In order to protect Arie’s vision, Dr. Hedayat proposed something that had never been done before at Children’s Wisconsin.

Plumbing of the brain

First, Dr. Hedayat would reroute the blood supply to Arie’s vision area. He would take an artery that fed blood to Arie’s scalp tissues on the back of her head, and connect it to the surface of her brain — cutting, moving and sewing arteries that are no more than 2 millimeters in diameter, roughly the size of a piece of angel hair pasta, with stitches that are more fine than hair. By redirecting (bypassing) blood from the scalp to the affected territory, blood flow can be maintained, which would help protect her vision. After the bypass, Dr. Hedayat’s partner would then do a traditional coiling procedure of the aneurysm.

First, Dr. Hedayat would reroute the blood supply to Arie’s vision area. He would take an artery that fed blood to Arie’s scalp tissues on the back of her head, and connect it to the surface of her brain — cutting, moving and sewing arteries that are no more than 2 millimeters in diameter, roughly the size of a piece of angel hair pasta, with stitches that are more fine than hair. By redirecting (bypassing) blood from the scalp to the affected territory, blood flow can be maintained, which would help protect her vision. After the bypass, Dr. Hedayat’s partner would then do a traditional coiling procedure of the aneurysm.

Think of it like bathroom plumbing. You have a main pipe bringing water from the basement to a bathroom, where it branches off to feed the sink, toilet and shower. All of a sudden, there is a leak in the pipe to the shower (an aneurysm). Instead of going into that pipe and fixing the leak, the bypass procedure takes the pipe that feeds the sink and moves it to feed the shower. Meanwhile, water no longer flows through the pipe with the leak.

“Her family was very much in favor of the plan,” said Dr. Hedayat. “They were all on board for it.”

Arie’s bypass took 4-5 hours. With the blood flow rerouted, Dr. Hedayat and his partner prepared to insert the coils into the aneurysm. During an intense brain surgery, you never want to be surprised by what you find. But when Dr. Hedayat was reviewing a CT scan of Arie’s brain between procedures to prepare for the coil, he was shocked to see that the aneurysm had closed by itself.

“It was probably that reversal of blood flow from the bypass that caused the aneurysm to clot off and shut down on its own,” said Dr. Hedayat. “And her vision wasn’t affected.”

“It's crazy, you have all this time to dwell. When she had surgery, she was under sedation, so you're just sitting there staring at her, hoping for the best,” said Tony. “But everybody was so supportive. We loved the nurses, everyone.”

The day after surgery, Arie was doing great — up and walking around, doing normal kid stuff. She spent a few weeks in the hospital recovering, first in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit and then in the Neurosciences Center where she was observed for spasm of her brain blood vessels which commonly occurs after aneurysm ruptures. She had a few headaches and did some physical therapy, but overall, recovery went smoothly and without incident.

The power of innovation

“First of all, her type of aneurysm is pretty rare where it involved a blood vessel going to the vision part of the brain. But then, to do this bypass with an artery from the scalp is even more rare. It had never been done at Children’s Wisconsin before. It was very much a customized treatment based on Arie’s problem and her anatomy,” said Dr. Hedayat, who is also an associate professor of neurosurgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin. “The reason a lot of people don't do this treatment is either they don't have the skillset or the equipment. But at a system like Children’s Wisconsin, we have both.”

“First of all, her type of aneurysm is pretty rare where it involved a blood vessel going to the vision part of the brain. But then, to do this bypass with an artery from the scalp is even more rare. It had never been done at Children’s Wisconsin before. It was very much a customized treatment based on Arie’s problem and her anatomy,” said Dr. Hedayat, who is also an associate professor of neurosurgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin. “The reason a lot of people don't do this treatment is either they don't have the skillset or the equipment. But at a system like Children’s Wisconsin, we have both.”

Thanks in large part to its affiliation with the Medical College of Wisconsin, which has been the academic partner of Children’s Wisconsin since 2000, families who come to Children’s Wisconsin have access to some of the country’s leading physicians. As an academic medical center, Children’s Wisconsin utilizes cutting-edge treatments, sets quality standards for patient care and furthers scientific concepts through research and clinical trials. In short, Children’s Wisconsin provides families with best care possible for their children.

“People always say how Children’s Wisconsin is a place you never want to be, but when you have to be, you're happy it's there. It’s true. It’s so nice to have that good of a medical center so close to home,” said Tony. “I talk about Children’s Wisconsin all the time and the great experiences we had.”

Just over a year removed from the surgery, Arie comes back to Children’s Wisconsin every few months to check on the aneurysm, and so far everything has remained normal and stable.

“It looks pretty pristine,” said Dr. Hedayat.

She’s had no long-term side effects from the aneurysm or the surgery. She's very much a typical 11-year-old girl. She just started middle school, she loves to paint, go on bike rides and take care of her bearded dragon, Cheeto.

“She’s doing great,” said Tony. “She’s just trying to have the most normal life as she possibly can.”