What would diabetes look like if it had a face?

Shari Liesch, an advanced practice nurse from Children’s Wisconsin-Fox Valley, posed that question to 254 patients with type 1 diabetes ages 4 to 18 as a way to better understand their experiences with the autoimmune disease.

“It was just an idea, a wonder on my part,” Liesch said. “And we got so many interesting responses.”

She received so many in fact that she is launching a study on June 24 that will go beyond just asking patients to draw a picture. In this in-depth, formalized study, she will interview participants and examine the meaning of their artwork.

“I want to better understand their lived experience with dealing with this disease that is interweaved in everything they do,” she said.

Diabetes, which the American Diabetes Association states affects about 208,000 Americans under age 20, is demanding to manage. For instance, patients must prick their fingers and take insulin shots four times a day, as well as go to clinic appointments every three months, according to Liesch.

Diabetes, which the American Diabetes Association states affects about 208,000 Americans under age 20, is demanding to manage. For instance, patients must prick their fingers and take insulin shots four times a day, as well as go to clinic appointments every three months, according to Liesch.

Liesch first started studying the connection between art and diabetes in 2014 when over the course of five months she asked patients at the start of their appointments to draw what they think the face of diabetes would look like.

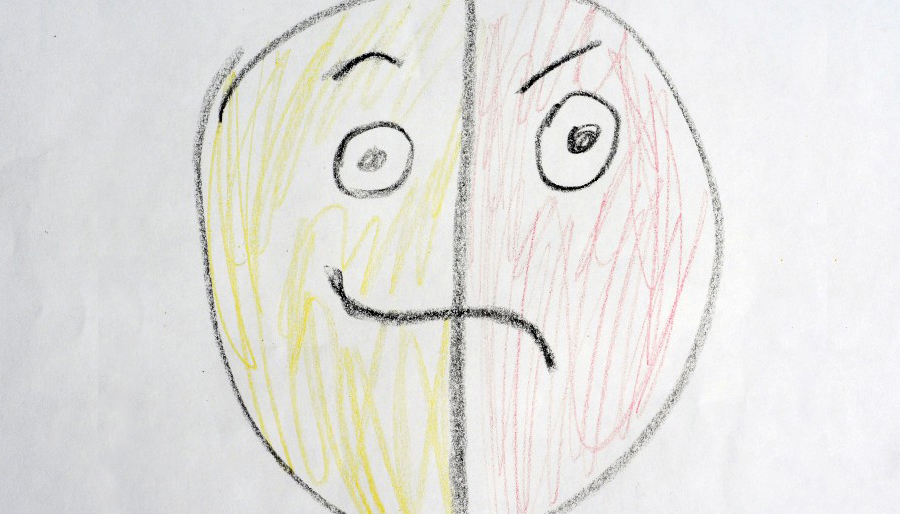

The most surprising theme she found in the drawings was split faces. In other words, several children depicted themselves half as they are and half as diabetes.

"Their faces were half smile, half frown,” she said. “One drew a human eye and a cat eye with the cat eye side having a fang. Another one had red horns in the midst of her hair.”

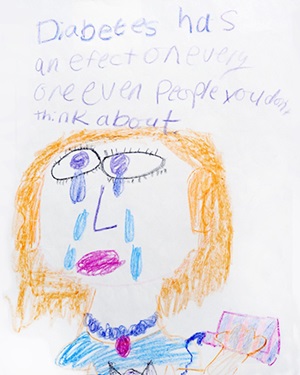

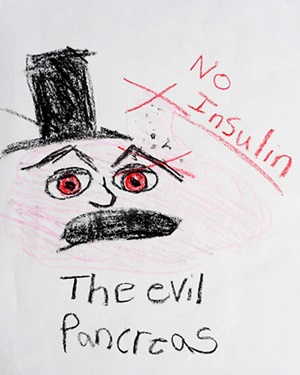

Liesch also received drawings that depicted devils, monsters and aliens. Others drew supersized insulin syringes, and one child even colored his whole piece of paper black.

Many other children drew pictures representing themselves when their blood sugar is low. When that happens, they need to immediately bring it back up or risk losing consciousness or suffering a seizure, Liesch said.

Another child depicted himself falling through the air, and later told Liesch his grandmother died from diabetes. Liesch had to explain to him that diabetes is something he needs to manage, but that he should not be afraid of dying from it.

While some drawings such as that one led to further conversations with patients about their feelings, Liesch overall did not speak in depth with the children about the drawings because she wanted to save the interviewing for the bigger research study.

Approved by the Children’s Wisconsin Institutional Review Board, the study will focus on 20 patients ages 8 to 15 with type 1 diabetes who are treated at the Children’s Wisconsin-Fox Valley diabetes clinic in Neenah, Wisconsin.

They will create three drawings and then be interviewed about the meaning of their artwork, their word use in describing it, and the meaning of color used.

The drawings, meanwhile, will be analyzed for overall content and computer analyzed for color use.

Additionally, participants will fill out surveys meant to help examine the relationship of drawings and color use with diabetes quality of life, intrinsic motivation and personality type.

Additionally, participants will fill out surveys meant to help examine the relationship of drawings and color use with diabetes quality of life, intrinsic motivation and personality type.

“I’m hoping to see if there’s any relationship between colors used in their drawings and how they feel, and see if there’s a correlation between quality of life and color used,” Liesch said.

Liesch will serve as the principal investigator on the study, and her co-investigators will be a nurse researcher employed at the pharmaceutical company Sanofi and an assistant nursing professor at University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh.

Two consultants will also work on the study: an art therapist and an advanced practice nurse from Children’s Wisconsin-Fox Valley.

Results from this study, which is expected to be completed by the fall, will guide future studies exploring the impact of drawing in type 1 diabetes visits over time, according to Liesch.

“If you better understand their lived experience, then you can target care in a way that matches their feelings,” she said. “It’s about meeting them where they’re at.”

Dr. Rosanna Fiallo-Scharer, the director of the diabetes program at Children’s Wisconsin, asserts drawing therapy is an interesting idea to gain insight into the youth experience of living with diabetes.

“Type 1 diabetes is a particularly tough chronic disease to live with because it’s so overwhelming for families to live with day to day,” she said. “You have to think about it every minute of the day pretty much. You don’t get a break from diabetes, and that can result in non-adherence to the treatment. So any kind of strategy that may result in improving or causing some relief in any way for these families would definitely be important.”

Liesch believes creating art has numerous benefits for patients, including expressing emotions that would otherwise be suppressed and helping to reduce stress and facilitate coping.

Liesch believes creating art has numerous benefits for patients, including expressing emotions that would otherwise be suppressed and helping to reduce stress and facilitate coping.

Liesch herself was so inspired by the patients’ drawings that she wrote a poem called “Ode to the ‘face’ of diabetes.” It is set to be published later this year in the American Holistic Nurses Association’s bi-monthly magazine Beginnings.

The poem explores all the different types of “faces” she encountered, and ends with her desire to learn more.

It started with a wonder, from one who cares,

“It” has been exposed, secrets revealed, more aware.

But instead of quenching, the wonder’s elevated,

Emotions, colors, looks; desire to learn inflated!