Have you ever heard the news of a crisis close enough to home that it made your stomach drop? Maybe it was a shooting at the mall just a few blocks away, or a school nearby in lockdown. Maybe you saw a headline and your heart started racing. Maybe you called a friend to check on them.

That’s the closest many of us have been to experiencing the terror of being a victim of violence. Unfortunately, many families and children have dealt with violence firsthand by simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time. With a shocking and record-breaking increase in violence in 2020 and now 2021, that experience is happening to more and more people. As the trend continues, violence and trauma approaches every one of us.

“There’s no longer a clear divide between those who are impacted by violence and those who aren’t. We’re all impacted by it now,” said Paula Roberts, director of Community Health at Children’s Wisconsin.

This is the second post in the Kids in the Crossfire series — a series of blog posts that will explore the complexity of violence. A puzzle with many pieces, violence doesn’t have one perspective or solution, but instead is an issue that requires many people and a lot of work to overcome. The series will explore different perspectives of individuals who respond to the call to serve victims and are impacted by violence, and different interventions to help break the cycle of violence. The goal for everyone is to prevent another record year of children being harmed by violent injuries.

Community Health and Project Ujima

A group of crime victim advocates, community navigators, nurses and therapists are facing the rise in violence head on. They’re a part of the Community Health team at Children’s Wisconsin.

While some at Children’s Wisconsin work to repair a physical wound (read about that in the first blog post in this series), a team of people who are part of Community Health help those impacted by violence begin to emotionally and mentally recover. Sometimes they’re involved even if there wasn’t a physical wound at all.

“You don’t have to receive a physical injury to be a victim of violence,” said Roberts. “Everyone involved, even children who witnessed violence and weren’t physically harmed, need to connect to health services immediately. It’s crucial to moving the whole family and community forward.”

The team helping those who have experienced violence is Project Ujima. Project Ujima, which operates under the overarching Community Health team, works to stop the cycle of violent crimes through crisis intervention and case management, social and emotional support, youth development and mentoring, mental health, and medical services. Children’s Wisconsin launched Project Ujima in 1996 in response to a growing number of victims showing up in the Emergency Department with gunshot and stab wounds.

“When a child comes to us due to violence or we’re asked to help a family, we act quickly because two very important things need to happen right away — stabilization and decreasing retaliation,” said Brooke Cheaton, Project Ujima manager.

Stabilization is a term the team uses to describe the many ways they try to help victims and their families cope with and begin to recover from the terror and trauma described earlier. Those involved might feel unsafe, scared to go to their homes, confused — they’re distraught. The crime victim advocates, nurse, mental health coordinator and therapist who make up the Project Ujima team help victims and their families process the trauma they’ve experienced and the feelings they’re having.

The cycle of violence is propelled by retaliation. Anger is an early emotion associated with grief, and anger can make people want to retaliate, or get back at those that caused them or their loved one pain.

“This is where our team is invaluable. They put the focus on the child who has been injured and try to intercept anger from those around them that turns into retaliation,” said Roberts. “But 2020 and 2021 are proving difficult in this area as well. Before the last year, we only brushed up against retaliation. In the last year, we’ve had so many homicides and nonfatal gunshot wounds, we’re seeing an intricate web of connectedness. We have to constantly ask if this case is related to the one we saw a couple days ago.”

A record-breaking year leads to another

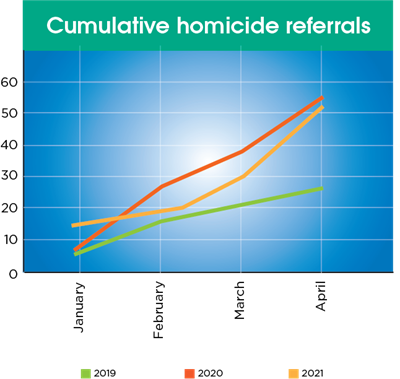

That connectedness is more likely as the number of violent injuries increases. The Project Ujima team worked with families from more than 201 homicides in 2020. And 2021 isn’t looking any better.

That connectedness is more likely as the number of violent injuries increases. The Project Ujima team worked with families from more than 201 homicides in 2020. And 2021 isn’t looking any better.

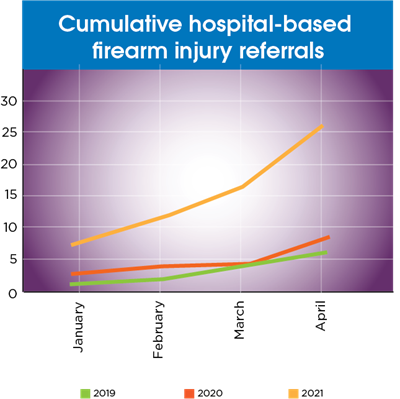

Teams within Children’s Wisconsin, as well as community partners such as the Milwaukee Homicide Review Commission, call on the Project Ujima team to help when a homicide occurs. These referrals to Project Ujima jumped from 8 in January of 2020 to 13 in January 2021. And hospital-based firearm referrals for Project Ujima have more than doubled each month this year when compared to last.

There’s no single, clear reason for this increase in violence. However, COVID-19 clearly made life more complex for families. Because of COVID-19, the Community Health team — specifically the community navigators on that team — saw more families in need of basic items like food and transportation, and they saw the complexity of what families were dealing with increase. While dealing with trauma related to violence, families were also facing sickness or even death in their family due to COVID-19, mental health needs, lost jobs, virtual learning for students…the list goes on.

There’s no single, clear reason for this increase in violence. However, COVID-19 clearly made life more complex for families. Because of COVID-19, the Community Health team — specifically the community navigators on that team — saw more families in need of basic items like food and transportation, and they saw the complexity of what families were dealing with increase. While dealing with trauma related to violence, families were also facing sickness or even death in their family due to COVID-19, mental health needs, lost jobs, virtual learning for students…the list goes on.

COVID-19 also impacted how the Project Ujima team worked with families, forcing them to be creative and innovative.

“Last year was like no other, so we had to help families like we never have before,” said Cheaton. “We struggled with not having as much of a physical connection with families, but quickly adjusted to virtual visits with them, learning how to ask new or different questions and starting the conversation differently than if we were in person.”

The team has described the last year as:

“Being tense for a year straight without a chance to recoil.”

“Experiencing the worst case you’ve ever worked on and bracing yourself for the next one.”

"Constant complexity.”

Yet, they also describe the families they work with as:

“Some of the most optimistic and uplifting people ever, even though they are facing unfathomable circumstances.”

“The most resilient people I’ve ever met.”

“Meeting these kids, you’d have no clue the trauma each of them has been through.”

“They give us hope.”

“Watching how they come together to support one another and offer hope no matter what stage they’re at is astounding, sheer greatness.”

Healing beyond the physical wound

True healing for everyone impacted by violence begins when you try to connect with them about options and support in a way that’s respectful and non-judgmental. Most often, the team is working with victims who did nothing wrong and had nothing to do with the incident that occurred. For example, it might be the kid next door to the house that randomly had shots fired at it who’s now scared to go to bed at night. That awareness and conversation among the community about the widespread impact of violence is an important first step for healing.

In addition, emotional and mental safety is key to healing. While some families may be able to consider moving, others cannot. And even if they could, it most often does not eliminate the stress, anxiety and fear a child feels after a violent incident. Safe environments will help a child begin to process what’s happening and heal. Places like summer camp are crucial.

"At Camp Ujima, a six-week summer camp put on by Project Ujima, kids don’t have to worry about being safe,” said Cheaton. “They can just be kids without fear or anxiety, and they can be around other kids who have had similar experiences. When summer camp starts, the kids are all quiet and don’t talk to each other, but by mid-summer, you can’t get them to get on the bus to go home because they don’t want to leave each other.”

Unity and understanding at these types of programs are irreplaceable. One program that’s proven to be a successful mental-health-based intervention is Hip Hop Therapy. It lets the kids and teens express their feelings using music, poetry and body movements. They learn how to use their own words to talk about what happened and their future.

“When we give these kids tools to express themselves, we can allow them to move at their own pace,” said Cheaton. “While their physical wound may heal up, we don’t know when they’ll be ready to start the healing process psychologically, so we listen, surround them with support and give them tools for when they’re ready.”

Prevention is key

Ideally, preventative programs in the community would be recognized for how important they are, supported with sufficient and sustainable funding, and have the resources to be effective in preventing violence in the first place.

“Our team supports preventative programs, but how we work with families is after an incident has occurred and we’re called in to help. If we could prevent violence from happening, the quality of life for everyone would be much better,” said Roberts. “We can’t have children in classrooms trying to learn when they’re in the hospital, or are worried about their safety or the safety of their family. Preventing them from these situations in the first place is necessary.”

The teams describe violence as everyone’s issue. It’s not something to be addressed by only Children’s Wisconsin, law enforcement or the community, but instead by all organizations and individuals working together.

Throughout Children’s Wisconsin, there are doctors, therapists, administrators, staff and others who understand it is not enough to be exceedingly good at treating the immediate result of the violence — the physical wound or psychological trauma. That is just a small sliver of that child’s whole experience with violence. It’s our vision for Wisconsin’s kids to be the healthiest in the nation, and to reach that goal we must help keep kids protected from violence in the first place.

In upcoming blog posts in this series, we’ll dig into the impact violence has on kids as they mature into adults.