“Mommy, my head hurts.”

It was November 2017. It was the first time Maria had ever heard her 4-year-old daughter, Rosemary, complain of a headache. Normally, a headache isn’t much cause for concern, but something compelled Maria and Roberto, Rosemary’s father, to take her to the nearest emergency room in Appleton.

Maria is thankful they did. After a quick examination, the doctor delivered the shocking news — Rosemary was having a stroke and had fallen into a coma. They recommended sending Rosemary to Children’s Wisconsin Hospital-Milwaukee.

When they arrived at Children’s Wisconsin, Maria said the medical team acted quickly.

“As soon as we arrived, they immediately took Rosemary for testing,” said Maria. That was when they first met Raphael Sacho, MD, a neurosurgeon at the Children’s Wisconsin Neurosciences Center. Dr. Sacho’s international neurosurgery career focuses on applying novel surgical techniques to the blood vessels of the brain. It’s experience he would heavily rely on for Rosemary’s case.

The first step was figuring what was causing the bleed in the back of Rosemary’s brain. Doctors did a CT scan of her head that showed some kind of mass that could be a blood clot, tumor or aneurysm. But it wasn’t clear, so they took an angiogram, an imaging scan of the veins and arteries. That still didn’t show the cause for the bleed. But it did show that Rosemary had multiple brain aneurysms.

A brain aneurysm is an abnormal weak spot on an artery or vein that bubbles and creates pressure on surrounding brain tissue or nerves. If it ruptures, it spills blood into the surrounding tissue. Smaller aneurysms, like Rosemary’s, do not always bleed. But if they do, it can result in brain damage or, in worse cases, death.

“It was a very difficult situation, Rosemary was in a coma, and we knew it was really bad,” said Maria. “Dr. Sacho spoke to us very calmly, and he told us he would do everything he could to make her better.”

“Most aneurysms affect those who are closer to the 40-60 years of age, those who were smokers, hypertensive or have a family history of brain blood disorders,” said Dr. Sacho, who is also an assistant professor of pediatric neurosurgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin. “Those with larger aneurysms usually have symptoms like vision or speech problems, processing and concentration disorders, loss of balance, and fatigue. Rosemary’s case goes against the grain for multiple reasons.”

But the story only gets more complex from there.

A unique case

“What we saw in the scans is she had multiple, unusual aneurysms in the front part of her brain, away from where the bleeding had happened in the back,” said Dr. Sacho. “These were unruptured aneurysms but immediately alerted us to the fact that something was abnormal.”

“What we saw in the scans is she had multiple, unusual aneurysms in the front part of her brain, away from where the bleeding had happened in the back,” said Dr. Sacho. “These were unruptured aneurysms but immediately alerted us to the fact that something was abnormal.”

Dr. Sacho and his team decided that the larger aneurysms required treatment.

In a surgery that lasted about three hours, Dr. Sacho had to open up Rosemary’s skull so he could place a surgical clip on several aneurysms. The overall recovery was long and Rosemary was in the hospital for nearly two months. Though Rosemary made a complete neurological recovery, the medical team never found the source or cause of the aneurysms.

In January 2018, one month after surgery, Dr. Sacho followed-up with another angiogram, which showed some new aneurysms had formed. These were small and Dr. Sacho decided to leave them alone for the time being. For two years, Rosemary came for regular check-ups and all seemed well. No headaches, no signs of trouble.

“I thought things were great and stable,” said Dr. Sacho. “But, more was to come.”

In January of 2020, once again, Rosemary started complaining of headaches. A routine MRI showed that a tiny aneurysm in the front part of the brain had grown dramatically, with two new aneurysm

s right next to it and six additional ones in the back of her brain.To make matters worse, the aneurysm that had previously bled and healed last time had reopened and was filling with blood.

“One aneurysm by itself is life-threatening,” said Dr. Sacho. “Having multiple aneurysms at this age is, to say it mildly, unique.”

Searching for a solution

Dr. Sacho knew he needed to do another surgery, but this time, due to the complex nature and difficult location of the aneurysms, he opted for a different technique. Dr. Sacho’s training is unique, in that he specializes in both open surgery and less invasive endovascular therapies that use thin tubes called catheters placed inside the blood vessels. Usually, providers can only do one or the other.

“Having both skillsets make providers less biased in terms of what therapy they will offer patients,” said Dr. Sacho. “That was one of the reasons I was so passionate to train in both, so I could deliver the therapy I thought was best for patients.”

For the second, less-invasive surgery, Dr. Sacho inserted the thin, flexible catheter into an artery in Rosemary’s leg and threaded it up to her brain. Dr. Sacho then placed tiny platinum wire coils into the aneurysms, which help them clot and stop them from filling with blood and growing. Over the next nine months, Dr. Sacho performed two additional endovascular procedures to treat four additional aneurysms.

Unfortunately, a few months after the second surgery, Dr. Sacho discovered the aneurysm in the back of the brain, off a main artery called the basilar artery, had actually pushed the coils out and was growing dramatically.

Following the fourth procedure, Dr. Sacho decided to get some additional opinions. He sent images of Rosemary’s aneurysms to other pediatric specialists at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Boston Children’s Hospital, Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis, and other leading institutions, to get their opinions on the case.

“Because of the unusual nature of Rosemarie’s case, we didn’t just rely on the opinions of local experts,” said Dr. Sacho. “We reached out to multiple other providers around the country to get the best opinions for this child.”

Dr. Sacho remembers how the head of Johns Hopkins’ cerebrovascular neurosurgery said, “Any treatment that you’ve done that’s kept her alive so far is a success.”

But Dr. Sacho was far from satisfied.

A very unusual method

Nine out of the 10 experts he consulted with recommended a procedure known as the pipeline flow diverter as the only way they could definitively treat the aneurysm. Even though she wasn’t rupturing, they said it was likely just a matter of time before the aneurysm burst.

Nine out of the 10 experts he consulted with recommended a procedure known as the pipeline flow diverter as the only way they could definitively treat the aneurysm. Even though she wasn’t rupturing, they said it was likely just a matter of time before the aneurysm burst.

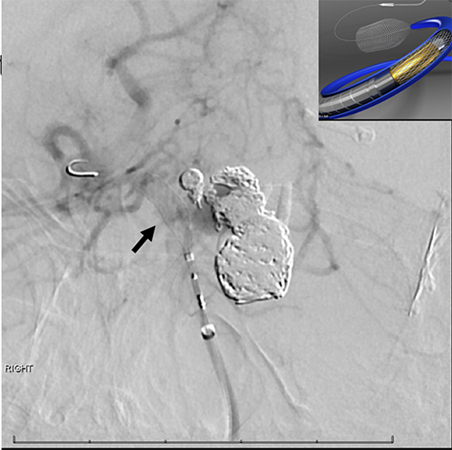

The pipeline flow diverter is another endovascular technique where instead of placing coils inside the aneurysm, a piece of cylindrical mesh is placed in the major blood vessel across from the aneurysm. It doesn’t get rid of the aneurysms immediately. Instead these pieces of mesh, known as stents, divert blood flow away from the aneurysms, increasing the possibility of clotting. In a few weeks or months, the aneurysm clots and is excluded from the circulation.

“I knew that there was no other way to really help this girl,” said Dr. Sacho.

A pipeline flow diverter in the top of the basilar artery has only been described in literature maybe a handful of times before in children, and perhaps only about 20 times in adults. A flow diverter in this location has significant risks.

“It’s a very unusual method,” said Dr. Sacho.

The reason it’s not done very often is because the tiny blood vessels coming off the top of the basilar artery are very important — they keep the clockwork of your body alive. These may become inadvertently obstructed as a result of the flow diverter.

“It’s the heart of your bloodwork,” said Dr. Sacho. “It’s very important. It controls your breathing. It controls your facial movements.”

A bright future

Dr. Sacho placed the pipeline flow diverter in the fall of 2020 during a three-hour procedure. Now 8 years old, Rosemary is four months post-surgery and doing great. The follow-up MRI scan showed the aneurysms have dramatically shrunk. The two small ones that were very difficult to treat are now gone, and the bigger one has shrunk by nearly a third and should close down completely in due time.

“Dr. Sacho is the best surgeon in the world,” said Maria. “I’m not sure where we would be right now if it weren’t for him, the nurses and everyone at Children’s Wisconsin.”

She still has a road ahead of careful surveillance and possibly more surgeries in the future, but for now, things appear to be stable.

“I really developed a connection with Rosemary. She’s been through a lot more than other kids her age, not many children can say they’ve had ten aneurysms and five surgeries before the age of 10,” said Dr. Sacho. “I personally don’t know how these parents do it. It requires so much strength. But now this young little girl has an opportunity to be healthy and live a pretty normal life.”