You’ve just heard one of the scariest things any parent can hear — something is wrong with your child’s heart. Suddenly, nothing makes any sense.

As you sit in that small consult room, your head is swirling with information you don’t yet completely understand — diagnosis, prognosis, survival rates, treatment options, volumes, second opinions, hospitalizations, surgeries, medications, appointments, specialists, outcomes, long-term care.

It can all be intimidating and overwhelming. In that moment — as you choose where you want your child’s care to be — would you know what questions you should ask?

1

To help assist parents through this uncertain time, the Pediatric Congenital Heart Association (PCHA) with the help of Herma Heart Institute at Children’s Wisconsin designed a Guided Questions Tool.

Transparency and empowerment

The PCHA is an advocacy group for families living with congenital heart disease that promotes “providing families with clear, consistent data so they can make a more confident, informed decision.” That’s exactly what the 17 questions in the tool are intended to deliver.

The PCHA is an advocacy group for families living with congenital heart disease that promotes “providing families with clear, consistent data so they can make a more confident, informed decision.” That’s exactly what the 17 questions in the tool are intended to deliver.

“When families receive a diagnosis, they get hundreds of pages of information thrown at them. It’s overwhelming and they understandably often remember next to nothing,” said Julie Lavoie, MSN, RN CPN, MS, RD. Julie is the quality improvement manager for the Herma Heart Institute at Children's Wisconsin and served as principal investigator for the Guided Questions project. “While every child is unique and not every question will apply to every family, the Guided Questions Tool does help to consolidate all relevant information into one, easier to digest package.”

As a long-time advocate for transparency and partner of the PCHA, Children’s Wisconsin has served as the lead test site for the Guided Questions project. Starting in 2016, the first phase of the project focused on surveying and consulting more than 100 parents and dozens of doctors, nurses and other caregivers throughout the country to compile a list of potential questions.

“Not only was Children’s Wisconsin a founding site but they also provided essential resources to ensure the early successes of the project and continue being the lead drivers today,” said Amy Basken, founding member and director of programs for the PCHA. “They continue to be the first to implement new and changing practices when it comes to public reporting and communicating with patient families.”

Personal experience

Amy’s quest for transparency and empowering families is born out of personal experience. It was January 2006 and Amy had just given birth to her third child, a happy and seemingly healthy little boy named Nicholas. They had actually already gone home when Nicholas’ pediatrician called with urgent news — something was wrong with Nicholas’ heart and he needed surgery right away. Sitting in her home, Amy couldn’t understand what she was hearing. All she kept thinking was, “Did he really need surgery?” and “Was he going to die?”

Amy’s quest for transparency and empowering families is born out of personal experience. It was January 2006 and Amy had just given birth to her third child, a happy and seemingly healthy little boy named Nicholas. They had actually already gone home when Nicholas’ pediatrician called with urgent news — something was wrong with Nicholas’ heart and he needed surgery right away. Sitting in her home, Amy couldn’t understand what she was hearing. All she kept thinking was, “Did he really need surgery?” and “Was he going to die?”

“Did he really need surgery?”

“Was he going to die?”

Years later, Amy now understands those were the wrong questions to focus on. In her fog, she wasn’t thinking about whether the hospital at which she gave birth was the best place to treat her son’s heart defect. She wasn’t thinking about specialized care or patient volumes or outcomes.

While everything ultimately worked out for her son, in 2013 Amy helped form the PCHA to make sure no other family has to go through the uncertainty and confusion she did. There is no removing the fear or worry from a congenital heart defect diagnosis — not completely — but it can be made easier.

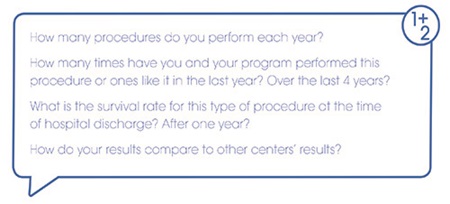

To help give parents some guidance, the PCHA Guided Questions Tool has 17 questions broken into three categories: information about your child’s cardiac center, information about your child’s hospital stay and looking ahead. The questions cover everything from, “How many procedures has the center performed each year?” to “Will I get to hold my baby before or after the procedure?” to “Are there other possible life-long problems that I need to watch out for?” — and everything in between.

“The Guided Questions help families identify a good center and help families focus on what’s important,” said Julie. “That was the essence of the project when it first started”

Providing answers

With the questions tried and tested with families in clinics, the next step was proactively providing answers to them. Children’s Wisconsin is one of only two institutions in the United States to have provided answers to each of these questions. Answers from Children’s Wisconsin, compiled in a printed booklet that's handed out to families at the time of a fetal heart diagnosis, were unveiled at the PCHA’s Fifth Summit on Transparency and Public Reporting in October 2018.

“Some centers are hesitant to share all of their data,” said Julie. “But we’ve always been really proud of our outcomes and believe in full transparency.”

2

Take, for example, the Glenn procedure, which is the second in a series of three surgeries for hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). HLHS is a serious birth defect in which the left side of the heart doesn’t fully develop. Children born with HLHS undergo three surgical procedures to repair the defect: the Norwood procedure shortly after birth, the Glenn procedure around 6 months old and then the Fontan procedure 18 to 36 months later.

According to published data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS), from 2014-2017 the Herma Heart Institute performed 45 Glenn procedures with a 100 percent in-house survival rate. But due to a nuance in how the STS collects data, the actual figure is 71 cases with a 93 percent survival rate.

According to published data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS), from 2014-2017 the Herma Heart Institute performed 45 Glenn procedures with a 100 percent in-house survival rate. But due to a nuance in how the STS collects data, the actual figure is 71 cases with a 93 percent survival rate.

“STS only counts an operation when it is the first one during a child’s hospital stay,” said Julie. “For kids with HLHS, they need two surgeries in the first six months of life. While most kids go home between these, our sickest and most medically fragile patients do not. Therefore, STS only counts their first surgery. That’s why the number of Glenn procedures according to the STS is lower than our internal data.”

Children’s Wisconsin could have easily just shared the STS figure and no one would have questioned it. But leadership at the hospital and the Herma Heart Institute insisted on providing the full data and context, even though the survival rate was lower.

“We felt it was a disservice to our families and in the spirit of truly being transparent it was important to share the full story,” said Julie. “It’s all about conversation and context. None of these questions and answers stand alone. This one piece of data shows how complex surgical outcomes are, and how important it is we partner with families to help them understand these numbers.”

Now, 13 years later, Nicholas is a healthy, active boy. But Amy’s quest continues. She will never forget those terrifying first weeks of his life. And still today her breath will escape her as she watches one of his soccer games and he slows down for a moment. She knows that feeling will never go away. She also knows that every day there are hundreds of families across the United States receiving that shattering news. While she felt lost in the aftermath of her phone call, these 17 questions can hopefully provide some assurance and guidance to those just starting their journey.