A baby no bigger than your hand.

With a heart the size of a grape.

And a hole in it the size of a pea.

That was the story of James Oglesby when he was born on March 10, 2019, more than 10 weeks early.

That was the story of James Oglesby when he was born on March 10, 2019, more than 10 weeks early.

At only 2 pounds, 4.3 ounces, James was incredibly small and fragile. To make matters worse, when he was 1 month old, his neonatologist, Vijender Karody, MD, discovered a problem with his heart.

1

A heart has two main arteries that deliver blood — the pulmonary artery takes blood to the lungs and the aorta takes blood to the rest of the body. When a baby is developing in utero, there is a small hole between these two arteries to aid in circulation. In a full-term baby, this hole is present at birth and closes on its own after a few days. But for many premature babies, that hole can remain open for weeks or months. That’s called a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). If large and left untreated, a PDA can cause difficulty breathing requiring the baby to need ventilation. In extreme cases, it can result in heart failure and even death.

In James’ case, his PDA was causing over-circulation of blood on the left side of his heart, making it swell to twice the size of the right side.

New treatment

For the past several years, Todd Gudausky, MD, an interventional cardiologist at the Herma Heart Institute at Children’s Wisconsin, had been keeping track of a new device being developed to treat PDAs in the tiniest babies.

For the past several years, Todd Gudausky, MD, an interventional cardiologist at the Herma Heart Institute at Children’s Wisconsin, had been keeping track of a new device being developed to treat PDAs in the tiniest babies.

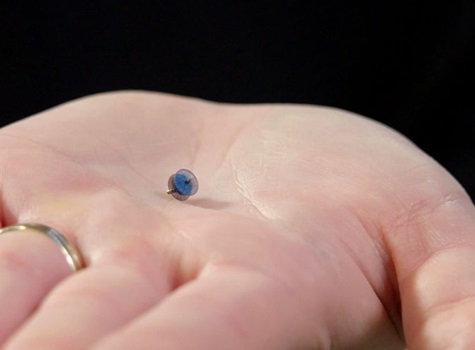

Known as the Amplatzer Piccolo Occluder, the device is essentially a small mesh plug that is inserted into the hole between the baby’s two main arteries. While used throughout the world for the last few years, it was only approved for use in the United States in January 2019. Dr. Gudausky immediately went to Minnesota for training and James became the first patient in Wisconsin to be treated with this new device.

Overwhelmed and exhausted with her new tiny infant in the NICU and five other boys at home, Lawanda doesn’t recall the moment doctors sat her down and told her about James’ heart defect. But she does remember the apprehension she felt when Dr. Gudausky and Dr. Karody suggested using the Piccolo for the first time.

“It was really scary. I didn’t have any information about another child having it done, so I was really worried,” said Lawanda. “But the doctors and nurses were all so wonderful and I trusted them to do what was best for James.”

On May 7, 2019, in a procedure that took about 30 minutes, Dr. Gudausky made a small incision in James’ groin and inserted a thin tube called a catheter with the Piccolo at the end. The catheter was then threaded through a vein into James’ heart and the Piccolo was placed in the hole, closing the opening.

2

“To do something for the first time is exciting and a little bit nerve-wracking,” said Dr. Gudausky. “However, this device is very similar to a number of other devices I have been using for 15 years. The main difference is its size so it’s better suited for really small infants and preemies. Before, we typically only closed PDAs in babies who were at least 8 pounds. James was around 4 pounds.”

Since James’ procedure, Dr. Gudausky has used the Piccolo on two additional patients, both even smaller than James. At the time of publication, Dr. Gudausky is the only doctor at Children’s Wisconsin (and in the state) trained to use the Piccolo, but fellow interventional cardiologist Susan Foerster, MD, is expected to get trained by the end of 2019.

Helping those most at risk

In the past, before the Piccolo was developed, babies born with a PDA had a couple care options depending on their size and the nature of the defect. For some, the PDA was small enough where no symptoms were present and no treatment was required. For babies born at 30 weeks or less, as James was, around 33 percent will have symptoms and need treatment. For babies born at less than 28 weeks, that number is as high as 66 percent.

In the past, before the Piccolo was developed, babies born with a PDA had a couple care options depending on their size and the nature of the defect. For some, the PDA was small enough where no symptoms were present and no treatment was required. For babies born at 30 weeks or less, as James was, around 33 percent will have symptoms and need treatment. For babies born at less than 28 weeks, that number is as high as 66 percent.

Premature babies are generally too small for a catheter procedure. In years past doctors either waited until the baby was older (which carried the risk for long-term respiratory issues due to the continued ventilation) or they performed a more invasive open surgery in which an incision is made between two ribs and the hole is sewn shut. In more recent years, however, surgical intervention had been replaced by treating the PDA with medication while waiting for it to close on its own.

“The Piccolo offers significant advantages. Whereas medication closes the PDA in about 50 percent of patients, with the Piccolo we can close the PDA in 100 percent,” said Dr. Gudausky. “During the procedure, we immediately see baby’s blood pressure go up and their blood flow improve. Once they received the Piccolo device, all three patients improved quickly and were all able to be weaned off ventilation within days. We’ve been very impressed at how well they’ve done.”

James’ surgery was on May 7. By May 12, he was off the ventilator. Without the Piccolo, Dr. Gudausky estimates James would have needed to remain on the ventilator for an additional 4-5 weeks until his lungs were strong enough to breathe on their own.

“Some of these kids get stuck on a ventilator for a very long time,” said Dr. Karody. “The Piccolo is a game changer for these tiny babies.”

It certainly was for James. Now he can just be a baby, without ventilation and without limitation.

“He’s doing good,” said Lawanda. “He’s come a long way.”