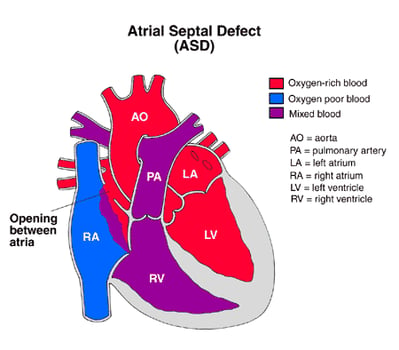

An atrial septal defect (ASD) is a heart defect that is present at birth (congenital). It happens when the fetal heart doesn’t develop properly in the first two months of pregnancy. There is a hole wall (atrial septum) between the two upper chambers of the heart.

A small opening in the atrial septum allows a small amount of blood to pass through from the left chamber to the right chamber. A large opening allows more blood to pass through and mix with the normal blood flow in the right heart. Extra blood causes higher pressure in the blood vessels in the lungs. The more blood that goes to the lungs, the higher the pressure.

The lungs are often able to handle the extra pressure for some time. After a while, however, the blood vessels in the lungs become damaged by the extra pressure.