Just 11 days after undergoing a grueling 10-hour heart transplant surgery, 2-month-old Hazel found herself back on a procedure table in the cath lab. She’d be back three weeks later and then yet again two months after that.

It wasn’t that there were complications with her transplant. Her donor heart was doing great, in fact. Each subsequent trip to the cath lab was to take a biopsy of her heart so doctors could test for rejection.

For those with life-saving heart transplants, receiving that donor organ is often seen by outsiders as the final step of a long journey. In reality, the journey never actually ends. Rejection is a constant concern for those living with an organ transplant.

For those with life-saving heart transplants, receiving that donor organ is often seen by outsiders as the final step of a long journey. In reality, the journey never actually ends. Rejection is a constant concern for those living with an organ transplant.

Every year, more than 5,000 heart transplants are performed worldwide. Of those, 10 to 20 percent will fail due to rejection. In the first year following the transplant, patients are tested for rejection up to a dozen times. After that, they must undergo regular surveillance biopsies for the rest of their lives.

1

The traditional biopsy to test for transplant rejection is expensive, invasive and labor-intensive. But now, thanks to a groundbreaking blood test developed by a husband and wife surgeon/scientist team, Mike Mitchell, MD, pediatric cardiothoracic surgeon at the Herma Heart Institute at Children’s Wisconsin, and Aoy Tomita-Mitchell, PhD, professor of pediatric cardiothoracic surgery and biomedical engineering at the Medical College of Wisconsin and investigator for the Children’s Wisconsin Research Institute, it no longer has to be.1

“For a patient who has just undergone a serious surgery — especially a child — having to undergo additional invasive procedures countless more times can cause a great deal of physical and mental stress,” said Dr. Mitchell. “This blood test takes that strain away.”

The old way vs. the new way

To perform a biopsy, a patient first has to be prepped as if going into surgery — if the patient is under 18 they’re put under general anesthesia; if they’re over 18, a local anesthesia is used. A small incision is made in the groin and a catheter (a thin tube with a tiny clamp on the end) is inserted into a vein or artery and threaded up to the heart. The small clamp then removes two small samples — about the size of a grain of sand — of heart muscle. This procedure, which is just the first step, generally takes about an hour.

To perform a biopsy, a patient first has to be prepped as if going into surgery — if the patient is under 18 they’re put under general anesthesia; if they’re over 18, a local anesthesia is used. A small incision is made in the groin and a catheter (a thin tube with a tiny clamp on the end) is inserted into a vein or artery and threaded up to the heart. The small clamp then removes two small samples — about the size of a grain of sand — of heart muscle. This procedure, which is just the first step, generally takes about an hour.

Once the specimens are obtained, they’re walked down to the lab where they’re split off into two, multi-step paths that involve cataloguing, drying, staining, encasing, cooling, slicing and setting before finally being sent to a pathologist for review.

With this new test, the process starts with a simple blood draw. No invasive procedure. No anesthesia. No fasting for 12 hours and arriving at the hospital at dawn. No waiting around all day (or night) for results. The sample is shipped overnight to the TAI Diagnostics lab in Wauwatosa.2

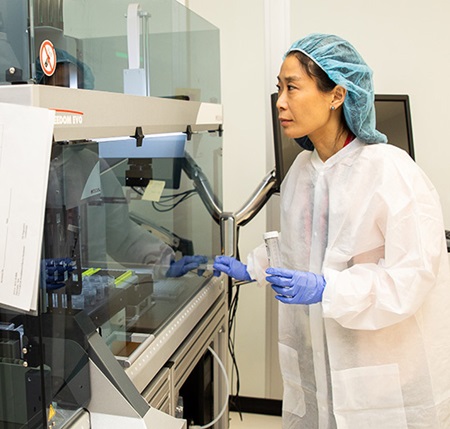

Once it is received, a robot extracts the DNA from the sample and then another machine is able to separate the donor DNA from the recipient’s DNA. Basically, the test is looking for how much donor DNA is present in the patient’s blood — a high level of donor DNA indicates rejection. Results are available within one business day.

“We have fragments of DNA that circulate in our blood,” said Dr. Mitchell, who is also a professor and section chief of pediatric cardiothoracic surgery at the Medical College of Wisconsin. “These fragments come from normal cell turnover, injury to the cells and inflammation. If you’ve had a transplant, a fraction of the DNA comes from the donor organ, and this fraction increases with injury to the donor organ.”

In addition to being faster, cheaper and less invasive than a physical biopsy, testing for DNA levels is more accurate. Just because rejection might not be present in one specific tissue sample taken from one part of the heart doesn’t automatically mean it might not be present in another part of the heart. Testing donor DNA levels in the blood can also detect rejection earlier, when it is more treatable.

The first patient

The inspiration for this test can be traced back to Emma. Emma was born in 2010 with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), a serious heart defect in which the left side of the heart fails to properly develop. The standard treatment includes three open-heart surgeries — typically around 2 weeks, 6 months and 2 years of age.

The inspiration for this test can be traced back to Emma. Emma was born in 2010 with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), a serious heart defect in which the left side of the heart fails to properly develop. The standard treatment includes three open-heart surgeries — typically around 2 weeks, 6 months and 2 years of age.

After her second surgery, Emma developed heart failure, which occurs in about 10 percent of all cases. When she was 9 months old, Emma was placed on the heart transplant list.

Despite that significant move by doctors, life began to stabilize for Emma and she was discharged from the hospital. But things took a serious turn almost two years later. While Emma was undergoing a cardiac catheterization to evaluate her for the third and final HLHS surgery, Dr. Mitchell discovered that the arteries and veins in her groin had collapsed from her multiple surgeries.

Without vascular access to her heart, doctors would not be able to perform the necessary biopsies to test for organ rejection when Emma ultimately received a transplant. That also meant she was a high-risk candidate and her transplant would be unlikely to be approved when considered.

Dr. Mitchell refused to accept that.

Proving a hypothesis

Half a decade earlier, Dr. Mitchell and Dr. Tomita-Mitchell developed another non-invasive, DNA-based blood test that could diagnosis Down syndrome in utero. Earlier diagnosis allows for earlier enrollment in therapeutic programs and prepares families for delivery. This test replaced what was known as the quad Alpha Fetoprotein (AFP) screen, which measures hormone levels from a maternal blood sample. According to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, the AFP had a false positive rate of about 5 percent.

Half a decade earlier, Dr. Mitchell and Dr. Tomita-Mitchell developed another non-invasive, DNA-based blood test that could diagnosis Down syndrome in utero. Earlier diagnosis allows for earlier enrollment in therapeutic programs and prepares families for delivery. This test replaced what was known as the quad Alpha Fetoprotein (AFP) screen, which measures hormone levels from a maternal blood sample. According to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, the AFP had a false positive rate of about 5 percent.

2

To confirm those often unreliable results, mothers needed to undergo what is known as an amniocentesis, a procedure that involves inserting a needle into the womb to collect a sample of amniotic fluid. In addition to causing unnecessary stress for the parents, complications of this invasive test resulted in the loss of thousands of unborn children annually. That new DNA test proved successful and they believed the same principals could be applied to donor rejection.

“We wanted to replace the AFP test. There is a lot of variability in measuring hormones in blood. We thought cell-free DNA would be a much more stable and accurate analyte. In the test for Down syndrome, we were able to quantify fragments of fetal DNA present in the mother’s blood,” said Dr. Tomita-Mitchell. “Mike hypothesized that, similarly, fragments of donor DNA might be present in a transplant recipient’s blood and, if so, that might help us determine if rejection was taking place or not. Mike and his colleagues applied for a grant from the National Institute of Health and we are now conducting a multi-site clinical study.”

Fortunately, Emma has not yet needed the blood test. After making incredible progress these past few years, she was officially taken off the transplant list in November 2017. But her mother knows that it’s likely a matter of when, not if. And knowing that this test now exists gives her great peace of mind.

“Nothing has been easy, and Emma has overcome so much to get where she is today. This test definitely takes away one of the biggest risk factor against her having a transplant,” said her mother. “I think that Emma inspired the test is wonderful. I’ve always felt that she has a purpose.”

1 At the time of publication, Dr. Aoy Tomita-Mitchell and Dr. Michael Mitchell are each inventors of the DNA-based test and each hold leadership positions at TAI Diagnostic, Inc. as the Chief Scientific Officer and the Chief Clinical Advisor, respectively.

2 At the time of publication, Children’s Wisconsin has a financial interest in TAI Diagnostics, Inc.