Through innovation and determination, Children's Wisconsin became one of the leading pediatric heart programs in the world.

Pediatric cardiac surgeon S. Bert Litwin, MD, had just finished his second attempt to painstakingly repair the tiny, walnut-sized heart of the 8-week-old baby girl, but it wasn't looking promising. It never was for babies born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) in those days. The babies essentially had half a working heart: their left ventricle was severely underdeveloped, depriving their bodies of vital blood flow. Many newborns died before they could even get to a surgeon willing to attempt a repair, and the ones who made it to surgery faced long odds. Until the 1980s, 95% of babies with HLHS died by the first month of life, and survival rates were only marginally better in the decade that followed.

|

| Photo: S. Bert Litwin, MD |

Leigh Herma's heart continued to beat in the Children's operating room that October day in 1987, but the medical team couldn't get her off the heart-lung machine without her blood pressure plummeting. They tried three, four times, before Dr. Litwin finally peeled off his surgical gloves and stepped away from the operating table.

“I've tried everything I can think of,” he declared. Resigned, he sat down and started writing: “Post-mortem death notice … pronounced in OR.” All that was left was the final time of death.

Across the room stood George Hoffman, MD, an anesthesiologist who had recently arrived from Boston. “Dr. Litwin, would you mind if I try a couple of things?” Dr. Hoffman asked. He adjusted medications until, amazingly, Leigh's blood pressure stabilized.

“In the face of imminent death, there's space for doing things that may have low likelihood of helping,” Dr. Hoffman would explain years later. “It's hard not to make an argument of ‘why not.’”

Dr. Litwin drew an X through his post-mortem note and put it in his pocket. Leigh had survived another day.

Persistence in the Face of Failure

The victory in the operating room that day was short-lived. A few weeks later, during a CT scan, Leigh died. Back then, nearly all the babies with HLHS died.

“I just remember the frustration of not being able to do a lot for those babies,” recalls Lori Grade, RN, who was one of Leigh's nurses. “If parents had a baby with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, they were told that there were limited surgical options, we couldn't predict how long their child would live, but that we would do everything we could.”

Dr. Litwin kept trying a procedure called the Norwood, which was the first of a three-stage process to reconstruct a functional heart for babies with HLHS by turning the right side of the heart into the main pumping chamber. Before the days of electronic records, nurses neatly recorded each attempt and failure by hand in a black three-ring binder, noting the patient's name, age, heart defect, surgery date and outcome. For the “hypoplast” babies, as they were known, each line ended with a red “D” for death. Between 1981-1992, 12 babies died.

“Then Dr. Litwin had the guts to take on the 13th patient,” recalls nurse-researcher Kathy Mussatto, RN, PhD. And baby Christopher, lucky No. 13, survived.

They hadn't turned the corner yet. Plenty of Ds still filled the patient logbook. But there was hope.

“Those were sort of the MASH days where everybody gets their adrenaline up because here comes the Norwood from the operating room,” remembers Maryanne Kessel, RN, MBA, a longtime nurse clinician who assisted during Leigh's surgery and who later became executive director of Children's Wisconsin's Herma Heart Institute.

The pressure ramped up further when surgeon James Tweddell, MD, joined the team in 1994. “One of the things that struck me in his first six to twelve months here was you could see him actively modifying his technique, not only operation to operation, but minute to minute,” says Dr. Hoffman, who is now the medical director of Anesthesiology for Children's Wisconsin, and chair and professor of pediatric anesthesiology at the Medical College of Wisconsin. “He was also very present in postoperative care. Together, we spent many nights at the Cardiac ICU, watching the hypoplasts at the bedside with a homebrew monitoring system we'd set up. We were obsessed.”

One day in the Cardiac ICU, Drs. Tweddell and Hoffman asked Dr. Mussatto: “What's our survival rate for the Norwood?” Dr. Mussatto, who would later become co-director of cardiac research, was the keeper of the logbook. She reported that early survival rates were around 75% — about the same as other heart programs. “I'll never forget the two of them saying, ‘That's not good enough. There's something we're missing,’” she recalls.

Revolutionizing Treatment of Pediatric Heart Patients

Even if babies survived their first surgery, many died 24 to 48 hours later. “All of a sudden the baby would code, and you wouldn't know why,” explains Lori Grade, who is now a patient care supervisor in the Cardiac ICU. “You couldn't see it coming.”

One day in 1996, Dr. Hoffman showed up with a catheter none of the staff had seen before. It measured systemic venous oxygen saturation (Sv02) — in other words, the oxygen level of blood coming back to the heart. It was like the canary in the coal mine: The Sv02 monitor predicted when an infant's circulation was deteriorating before other vital signs were affected.

“What they discovered was children are really deceptive and maintain blood pressure and arterial oxygen saturation while the circulation fails,” Kessel explains. “And in fact, you can have too good of a saturation, and that describes a certain physiology that isn't balanced for these kids.”

For post-Norwood babies with just a single “pipe” leaving the heart, balance was critical. In those days, the standard procedure everywhere was to keep HLHS babies literally blue — to adjust the pulmonary vascular resistance so that less blood went to the lungs and more went to the rest of the body. “Here you had this critically ill child who is trying to recover from a remarkably stressful event, and you're manipulating their oxygen supply without adequate information. But it was the only way people could keep the kids alive,” Kessel explains. “Our team said, let's not play with pulmonary vascular resistance, let's fix systemic vascular resistance, and that way the baby's oxygen level can be higher and we get good cardiac output. The strategy was guided by the additional continuous data that SvO2 monitoring provided. So the doctors started using drugs that managed systemic vascular resistance. At the time, it was heresy. But that became ‘the Milwaukee way.’”

Photo left to right: Kathleen Mussatto, RN, PhD, Maryanne Kessel, RN, MBA and Lori Grade, RN standing inside the cardiac intensive care unit at Children's Wisconsin.

Around the same time, Dr. Litwin decided to try Phenoxybenzamine, a medication used to balance pulmonary and systemic blood flow in adults. It worked. “There was a bit of a learning curve, but we saw our survival go from 75-95%,” Dr. Mussatto says. “It sort of shook the world.”

Soon, other programs around the world had adopted “the Milwaukee way.” That willingness to break with tradition would define Children's heart program.

“It's that confidence and innovation and determination that really has been a cornerstone of this program,” Kessel notes. “We're now developing a much more sophisticated innovation program around quality outcomes and research, but that's part of our DNA. When new members joined this team, Dr. Litwin would always say ‘Lead, follow or get out of the way.’ We're here to make a difference, and it's not like the kids have little things wrong with them — these are severe, life-threatening conditions. The stakes are high.”

Pioneering Monitoring Protocols Push Survival Rates Even Higher

But early survival wasn't enough. Many babies would go home and die during the interstage period between their first and second surgeries. The slightest change — dehydration from a common virus or an obstruction in the heart repair due to a baby's growth — could lead to sudden death. “I can't put up with this anymore,” Dr. Mussatto recalls Dr. Tweddell saying. In 2000, he decided to send every baby with HLHS home with a scale and pulse oximetry monitor so parents could track growth and oxygen saturation levels. As soon as something changed, parents were instructed to call the monitoring program team. “At first a lot of cardiologists were skeptical, but it changed interstage mortality from 15% to 0%,” Dr. Mussatto says. “The cardiology nurse practitioners, especially Nancy Rudd, PNP, were absolutely essential to the program.”

The surgeons moved up the second surgery when a baby showed signs of trouble, and that's how they discovered that they could safely operate at four months of age instead of six months. And it wasn't long before cardiac programs around the world were implementing their own home monitoring programs. A new standard set again by Children's.

In 2001, Children's pioneered the use of near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) monitoring, a noninvasive way to measure the oxygen going to the vital organs. The standard practice was to apply both probes to a patient's forehead to monitor the brain, but because Dr. Hoffman couldn't fit two probes on an infant's tiny forehead, he put one over the baby's kidney instead. That simple tweak yielded important insights into patients' oxygenation and blood flow.

“You're going to see changes in those two organs long before you're going to see changes in pulse oximetry or blood pressure,” Grade explains. “So that made a huge difference in our ability to intervene before it gets too far.”

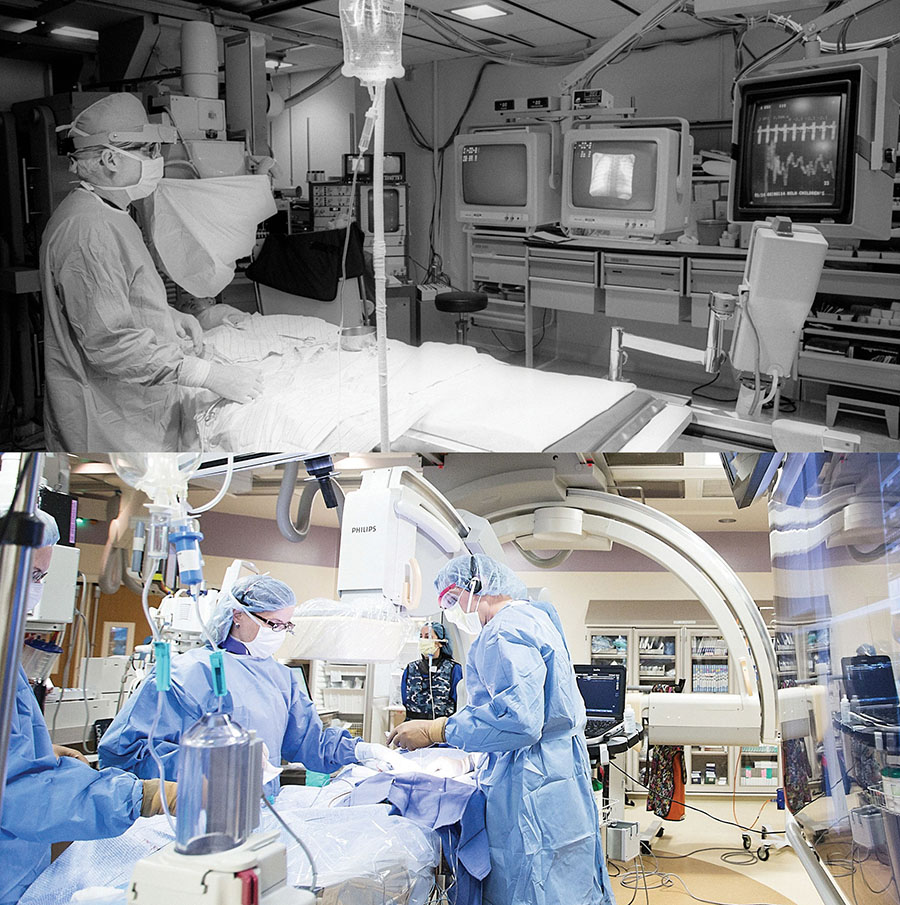

Photo: Children's Catheterization Lab in 1986 (top) and in 2016 (bottom)

The team discovered that kids who had better NIRS numbers did better long term, too. Together, the advancements in monitoring — from Sv02 and NIRS in the hospital to the interstage monitoring at home — transformed survival rates for a condition once seen as a death sentence. “How we moved the dot for hypoplastic left heart syndrome was recognizing that the usual measures that people were using to assess circulation were not adequate to keep children out of danger, to prevent the rapid cardiac deterioration that often resulted in cardiac arrest and death,” Dr. Hoffman says.

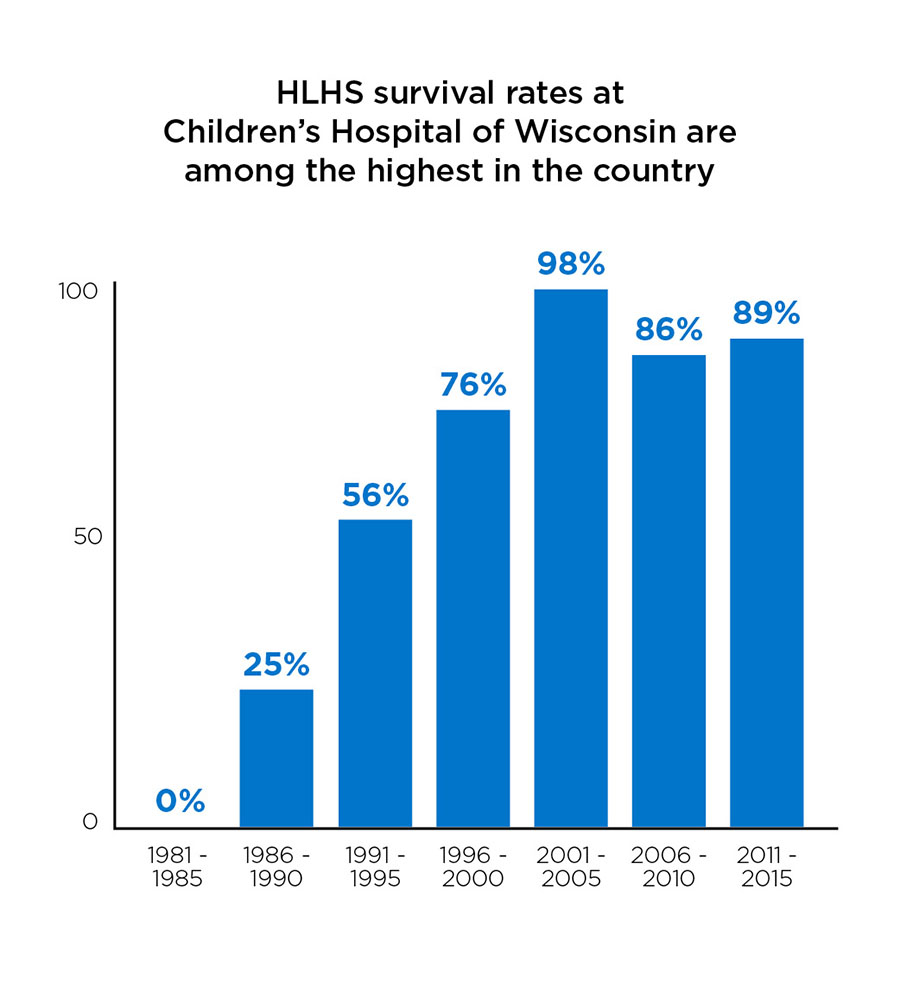

2001 was another milestone: it was the first year that Children's Wisconsin had a 100% survival rate for HLHS. While not every year has zero mortality, Children's continues to have among the best published outcomes for HLHS in the world.

And HLHS patients aren't the only ones who have benefited. “Taking care of newborns with complex heart conditions was like trying to get to the moon,” Kessel explains. “Look at all the things that were discovered because NASA had to figure out how to do a really complicated thing. We found that all of the surgical pathways for even the simplest of surgeries benefited because the anesthesia and critical care teams managed things more efficiently. So survival rates for all heart conditions went up.”

Focus Turns to Quality of Life

So babies were surviving. But were they thriving? Worried parents would grill Dr. Mussatto about their children's post-surgical prospects: “Is she going to be OK? Is he going to ride a bike? Is she going to be able to have a baby some day?” A mother herself, Dr. Mussatto understood. “I don't care about the gradient across the pulmonary valve. As a new mom, those are the questions I'd have, too,” she says.

And the early research showed that parents were right to be concerned about their children's development. “For a long time I don't think people made the heart-brain connection. They thought this was an isolated problem and that everything else looked fine,” Dr. Mussatto says. “It was a real eye-opener to realize that these children had not only developmental issues, but behavioral and social issues as well.”

To test patients' visual-motor skills, grade-school children were asked to reproduce a drawing. The kids who had undergone surgeries for HLHS and other single-ventricle defects as infants couldn't do it — their drawings were a Picasso-esque jumble of disjointed elements. The team started to think about strategies to protect kids' delicate brains during complex surgeries.

At the time, the standard procedure was to drastically cool a baby's body temperature — known as deep hypothermic circulatory arrest — and then shut off the bypass pump while the surgeon repaired the heart. In 2001, Children's adopted an alternate technique called antegrade cerebral perfusion, which maximizes blood flow to the brain during surgery. It makes the operation more difficult, but the Herma Heart Institute researchers found that the payoff was worth it: children who underwent surgery using the new technique scored in the normal range for visual-motor skills years later.

In 2007, Children's launched the world's first neurodevelopmental follow-up program for heart kids. “We don't wait for problems to occur,” Dr. Mussatto explains. “And if there are issues, we make sure children and families get connected to the support and resources they need.” Today, every child who has heart surgery is automatically enrolled, and similar programs have popped up around the country. A more recent addition is the Herma Heart Institute's School Intervention Program, which advocates on behalf of patients and families as kids return to school.

These quality of life programs aren’t billed to insurance and depend on philanthropic support. “But it's just the right thing to do,” Dr. Mussatto notes.

Over the years, survival rates weren't the only thing that grew. The heart team went from just a handful of staff to three surgeons, nearly 30 cardiologists, 11 cardiac anesthesiologists, eight cardiac intensivists, and more than 200 support staff. It earned the top, three-star ranking from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and moved up to No. 5 in U.S. News & World Report's rankings of pediatric cardiology programs. Twenty other heart programs, including seven from outside the United States, have visited to see how the Herma Heart Institute operates.

“It's always felt like a team approach,” Dr. Mussatto says. “It's never just been about a brilliant surgeon or a doctor in the critical care unit.”

And families have been a key part of the team. After Leigh Herma passed away in 1987, her parents, John and Susan, showed up a few weeks later with Thanksgiving dinner for the ICU staff. Their next gift was a rocking chair. During the past 30 years, the family has contributed more than $25 million to support the heart program. Throughout that time, their gifts have intentionally expanded the research agenda for pediatric congenital heart disease and advanced the transformation of clinical care through the addition of technology like ECMO machines and ventricular assist devices. Today, the Herma Heart Institute bears their family's name in recognition of their generous support.

“We are proud of the vision and execution of the Herma Heart Institute team over the past 30 years,” Susan Herma says. “To be named the fifth best heart program in the nation is an achievement that many people have worked very hard to reach. We have said all along that our No. 1 objective is to save every child and help them to grow into healthy adults.”

“We know that so much more needs to be accomplished,” John Herma adds, “and we are thrilled with the team today that will continue to improve medical innovation.”

A New Vision: Eradicating Congenital Heart Disease

Today, the Herma Heart Institute's survival rate for the Norwood procedure is around 89%, compared with 75% at most other programs nationwide. The institute's survival rates for the second and third HLHS surgeries are even higher: 94.5%for the Glenn procedure and 100% for the Fontan procedure. However, the right ventricle isn't designed to pump to the body for a lifetime, and children who survive the early surgeries often require heart transplants later in life. The oldest HLHS survivor in the world is just over 30.

“We will continue to learn more about what we have done and what we will be doing based on follow-up of patients, and that's really important,” Dr. Hoffman says. “Even though some of these approaches changed 15 years ago, the story keeps unfolding.”

On a recent summer day, the Cardiac ICU was quiet except for the steady beep, beep, beep of machines. A tiny infant slept in an isolette. A dad helped an older baby sit up in a chair. Parents hovered at the bedside of a child on life support. In the hybrid catheter lab down the hall, a child got a new valve. And elsewhere in the hospital, researchers continued to work on innovations related to everything from improving ventricular assist devices to mapping the molecular pathways of heart disease so scientists can develop new therapies.

“That's the goal of medicine: continually improve until you can eradicate disease,” Kessel says. Eradicating heart disease is a lofty goal, and it won't be easy. But the Herma Heart Institute team has never backed down from a challenge.

How You Can Help

It's through the generous support of people like you that we can continue to provide children with the best care possible. Help us help kids by donating to the Herma Heart Institute at Children's Wisconsin today! If you would like to speak with someone in the foundation about ways you can help, please call us at (414) 266-6100.