Jackson Radandt has been an anomaly his entire 21 years of life. On Easter Sunday in 2001, he was born weighing 8 pounds, 6 ounces, and perfectly happy and healthy — or so it appeared.

When Jackson was 5 days old, his mom, Melissa, noticed he felt cool to the touch, easily became fussy and wouldn’t nurse. Melissa also noticed Jackson was making a funny noise every time he exhaled. Gravely concerned about the breathing issue, Melissa and her husband, Jason, took Jackson to an emergency department near their home in Manitowoc. It didn’t take long for doctors there to realize that Jackson’s heart was severely compromised. After being transferred to a hospital in Green Bay, doctors there ultimately called for a transport to the Herma Heart Institute at Children’s Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

Doctors at Children’s Wisconsin diagnosed Jackson with hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), one of the most complex congenital heart conditions. HLHS is uncommon, affecting about 1 out of every 3,841 babies born in the United States each year, and very serious. The condition is characterized by small, underdeveloped structures on the left side of the heart, most critically an underdeveloped left ventricle. This chamber is normally very strong and muscular so it can pump blood to the body. When the chamber is small and poorly developed, it doesn’t function effectively and cannot provide enough blood flow to meet the body's needs. For this reason, an infant with HLHS cannot live without surgical intervention.

Treatment for HLHS requires highly specialized congenital heart surgeons to rework the baby's circulatory system through a series of three open-heart surgeries (Norwood, Glenn, and Fontan procedures) staged over a span of about three years.

Jackson had his Norwood procedure when he was just 10 days old, and successfully completed all three operations several months after his 2nd birthday.

Jackson feels he had a fairly normal childhood from ages 3 to 11, complete with friends, non-contact sports and success in school. While his condition did cause him to tire easily, it didn’t affect him in a serious way.

These types of medical advancements are possible because Children’s Wisconsin is an academic medical institution. Since 2000, the Medical College of Wisconsin has been the academic partner of Children’s Wisconsin, giving patient families access to the latest research and cutting-edge treatments.

A shocking turn of events

At a routine clinic visit when Jackson was 11, he and his family received shocking news — Jackson was in end stage heart failure. While that’s expected at some point for kids born with HLHS, he hadn’t been showing any initial outward signs. Unfortunately, his condition deteriorated rapidly and within a month he was admitted to the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit (CICU) at Children’s Wisconsin. A few days after that, doctors informed the family that Jackson would most likely need a heart transplant. On Oct. 23, 2012, Jackson was placed on the transplant list.

At a routine clinic visit when Jackson was 11, he and his family received shocking news — Jackson was in end stage heart failure. While that’s expected at some point for kids born with HLHS, he hadn’t been showing any initial outward signs. Unfortunately, his condition deteriorated rapidly and within a month he was admitted to the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit (CICU) at Children’s Wisconsin. A few days after that, doctors informed the family that Jackson would most likely need a heart transplant. On Oct. 23, 2012, Jackson was placed on the transplant list.

“I went from being able to play with kids at recess to being bedridden and not able to walk across the room in a very short period of time,” said Jackson.

After two months of medications and therapies, Jackson’s condition continued to worsen. On Dec. 23, 2012, Ronald Woods, MD, a pediatric cardiothoracic surgeon with the Herma Heart Institute, surgically placed an experimental device in Jackson’s chest called the Heartware Ventricular Assistant Device (HVAD). The HVAD is a mechanical pump implanted in the heart to help blood flow in people with weakened hearts. The device was necessary to stabilize Jackson until he could receive a heart transplant. He was the youngest patient who had undergone a Fontan surgery to receive an HVAD in the United States. While it was terrifying for Jackson’s parents to utilize an experimental treatment, they had to place Jackson in the best possible position to accept a new heart when one became available.

In fact, Jackson’s health improved so significantly that, after two months, he was able to go home with the HVAD machine — another first in the world. Even though he still had frequent visits to the hospital and was under constant monitoring, Jackson thrived at home. He gained weight, grew taller and eventually went back to school.

On May 20, 2013, Jackson’s family received a call that there was a heart for him, and it was a perfect match. Within three hours of receiving the call, Jackson was in the operating room getting prepped. He had just turned 12 years old. Jackson was discharged only 11 days later and couldn’t believe how different he felt. He was the healthiest he had ever been in his entire life, and physically he could feel the difference. He was able to join the basketball team and participate in physical activities without tiring quickly — things he had never been able to do before.

Jackson’s life changed in another dramatic way as well — due to his renowned use of the HVAD machine, he was invited to give speeches about his experience at conferences and galas across the country. In 2015, at the age of 14, he was invited to be a presenter at the American College of Cardiology as faculty. In 2018, he published an editorial about the experience in the journal Pediatric Cardiology.

A family connection

It’s no surprise, then, that Jackson and his family remained interested in cardiac research and innovation, and enrolled in genetic studies at Children’s Wisconsin.

It’s no surprise, then, that Jackson and his family remained interested in cardiac research and innovation, and enrolled in genetic studies at Children’s Wisconsin.

“Part of our interest was general curiosity to learn how and why congenital heart disease occurs around our family,” said Jackson. “But we also wanted clinicians to have a better understanding of congenital heart defects so we can advance science and therapies to provide better quality care to future generations.”

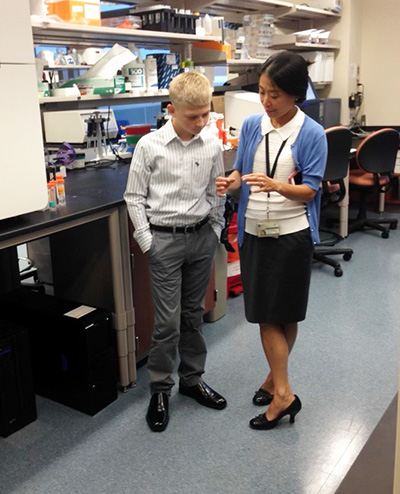

Aoy Tomita-Mitchell, PhD, an investigator with the Children's Research Institute and professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin, and her husband, Michael Mitchell, MD, a pediatric cardiothoracic surgeon at Children’s Wisconsin, came to Wisconsin in 2006 on a mission to find a better way to repair HLHS. They didn’t want babies to just survive, they wanted them to live a normal life.“From a research standpoint, we’re very interested in trying to understand how the malformation arises in the first place,” said. Dr. Tomita-Mitchell. “One of the best ways to do this is to study multiple family members.”

Thanks to families like Jackson’s who have enrolled in family pedigree analyses, the Mitchells have thousands of carefully prepared and characterized samples from hundreds of patients and their families.

“We’ve been able to look at several generations of family members who were affected with malformations and use new technologies like next-generation sequencing to find patterns,” said Dr. Tomita-Mitchell. “We found rare, often novel genetic variants in a heart muscle protein called the MYH6 gene in about 10 percent of cases.”

To determine if the variants were responsible for the disease, they used CRISPR gene editing technology to add the abnormal variant to cardiomyocyte cells (heart muscle cells) that didn’t carry it and removed the variant in cells that did carry it. Removing the variant “rescued,” or cured, the cellular dysfunction, while adding it to normal cells caused abnormal development. These results were published in Frontiers in June 2020.

“We are now able to test drugs in grown cardiomyocytes to see if they’re effective or if a patient might be more responsive to one drug over another. Eventually, we might even be able to treat infants prenatally,” said Dr. Tomita-Mitchell. “Families like Jackson’s have moved the field forward.”

These types of medical advancements are possible because Children’s Wisconsin is an academic medical institution. Since 2000, the Medical College of Wisconsin has been the academic partner of Children’s Wisconsin, giving patient families access to the latest research and cutting-edge treatments.

A unique research opportunity

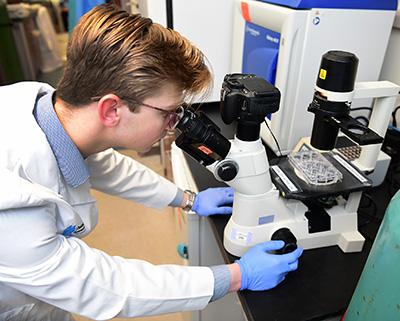

During the summer of 2021, Jackson got a first-hand look at how far research has advanced the field of congenital heart disease. As an incoming junior at Marquette University, he was able to enroll in a three-month program where he was placed in a Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) research lab. Jackson chose to work with the Mitchells on a collaborative bioengineering project with Brandon Tefft, PhD, an assistant professor in Biomedical Engineering at MCW.

During the summer of 2021, Jackson got a first-hand look at how far research has advanced the field of congenital heart disease. As an incoming junior at Marquette University, he was able to enroll in a three-month program where he was placed in a Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) research lab. Jackson chose to work with the Mitchells on a collaborative bioengineering project with Brandon Tefft, PhD, an assistant professor in Biomedical Engineering at MCW.

Jackson learned about bioprinting and also performed cell and cardiomyocyte research, including measuring beats, tracking the movement of cells, and monitoring rates of gene expression.

“I really got to dive into the research of my own disease, which was fascinating and powerful,” said Jackson. “It was very interesting to see how far things have come from the time I was born. Less than 25 years ago, most children with an HLHS diagnosis died before their 1st birthday.”

Dr. Tomita-Mitchell said they’ve never had a researcher who was also a research participant.

"We were thrilled to support Jackson’s interest and expose him to bioengineering and cardiac research,” said Dr. Tomita-Mitchell. “As someone who was also a research participant, he was able to provide insight in ways we wouldn’t have thought of. He was a wonderful team member.”

Thankfully, many babies will benefit from the research advancements Jackson contributed to.

“This type of effort is only possible through the wholehearted partnership of patients, clinicians and researchers at Children’s Wisconsin, the Herma Heart Institute, Marquette University and the Medical College of Wisconsin,” said Dr. Tomita-Mitchell. “We feel certain that this collaboration will result in greater understanding, and eventually, to additional treatment options for patients with HLHS.”

While Jackson isn’t entirely set on his future career path, there’s one thing he knows for sure — medical school is on the docket.