On Dec. 5, 2019, Lyndsi and Tom Godat and their 5-month-old daughter sat down with their cardiologist, Dan McLennan, MD. Though the meeting was every parent’s worst nightmare, he and the family quickly formed a deep and unbreakable bond that has carried the Godats through some of the hardest moments of their lives.

Lyndsi and Tom are from Clinton, Iowa, a small city on the Mississippi River about three hours east of Des Moines. During her pregnancy, Lyndsi’s doctor was 90 minutes away in Iowa City. It was there, at Lyndsi’s 20-week ultrasound, where doctors discovered her baby’s heart wasn’t developing properly. The baby was ultimately diagnosed with tetralogy of Fallot, a rare and serious — but ultimately treatable — combination of four different heart defects.

On July 21, 2019, Maisy Irene Godat was born. When she was 10 days old, Dr. McLennan performed a minimally invasive procedure to implant a stent in her heart to help improve blood flow. That would be a temporary fix with the hope of doing a corrective open-heart surgery closer to her 1st birthday. From there, everything seemed to be going fine.

On July 21, 2019, Maisy Irene Godat was born. When she was 10 days old, Dr. McLennan performed a minimally invasive procedure to implant a stent in her heart to help improve blood flow. That would be a temporary fix with the hope of doing a corrective open-heart surgery closer to her 1st birthday. From there, everything seemed to be going fine.

But on that morning in December, Maisy had what Lyndsi and Tom referred to as a spell. Maisy turned blue and her blood oxygen levels dropped to the low 60s — normal is in the mid-90s. This can happen in kids with tetralogy of Fallot when the blood isn’t being effectively circulated throughout the body. Concerned, but not totally unprepared, Lyndsi and Tom loaded her in the car and took her to the children’s hospital in Iowa City.

The normal tricks — elevating her legs, morphine IV— weren’t working, so doctors ordered a CT scan. That’s when they discovered what they had feared. The spell wasn’t related to Maisy’s tetralogy of Fallot. She, in fact, had developed another, even more rare and serious heart defect: Pulmonary vein stenosis (PVS).

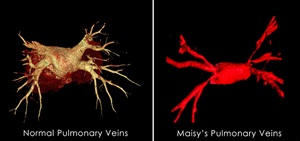

PVS is a narrowing of some or all of the pulmonary veins that carry oxygen-rich blood from the lungs to the heart. For a healthy newborn, the pulmonary veins are 4-6 millimeters thick — about the size of a pencil eraser. When Maisy was diagnosed with PVS, her veins were the size of a strand of spaghetti. Over time, as the heart has to work harder to pump enough blood throughout the body, Maisy will experience severely high blood pressure and, eventually, heart failure. While there are treatments to alleviate symptoms, the only “cure” is a heart and lung transplant.

It was Dr. McLennan, who specializes in PVS, who broke the news to Tom and Lyndsi.

“I remember Dr. McLennan telling us what was going on,” said Tom. “He was almost in tears. That meant a heck of a lot, you know.”

A special bond is formed

“Maisy was born with tetralogy of Fallot, and the combination of that with pulmonary vein stenosis is extremely rare,” said Dr. McLennan.

“Maisy was born with tetralogy of Fallot, and the combination of that with pulmonary vein stenosis is extremely rare,” said Dr. McLennan.

The severity of PVS can range quite a bit depending on how narrow the veins are and how many of the pulmonary veins are affected. In Maisy’s case, all of her veins had severe narrowing.

Given Maisy’s size and the severity of her stenosis, most of the doctors didn’t think it was safe to treat. In fact, they didn’t think she’d live more than a few more weeks. Dr. McLennan disagreed.

A few days later, he performed a cardiac catheterization. In this minimally invasive procedure, Dr. McLennan threaded a small metal wire into a vein in Maisy’s groin and fed it up to the affected pulmonary veins. He then inflated a tiny balloon inside each vein in order to stretch it out and increase the blood flow.

“Dr. McLennan has been aggressive,” said Tom. “I feel like other doctors wouldn't have had the same tenacity to go after it as he did.”

“It wasn’t that they didn’t want to help,” added Lyndsi, “they just didn’t know how to.”

While this treatment helped, relief is only temporary. As Maisy grew, she required additional procedures every four to six weeks. All told, she’s had 14 catheterizations in her 2 years of life.

In late May 2020, when Maisy was 10 months old, her tetralogy of Fallot was getting worse. Though her doctors had hoped to make it until her 1st birthday, she couldn’t wait for surgery any longer. Dr. McLennan referred her to a surgeon in Houston.

While the surgery was a success, shortly after the family returned to Iowa they received some unexpected news. Dr. McLennan had accepted a new job at the Herma Heart Institute at Children’s Wisconsin and would be leaving Iowa.

“I cried,” said Lyndsi. But the two parents didn’t have a moment’s hesitation. They knew they were going to follow Dr. McLennan the 200 miles to Milwaukee.

“I was like, ‘I guess we’re going to Milwaukee,’” said Lyndsi. “Dr. McLennan was the only one who was advocating for Maisy. He bonded with her and was always very honest. He did everything he could and always tried to remain hopeful, while still being realistic.”

“I can't say it was a tough decision,” said Tom. “There are a lot of reasons that led us to follow Dr. McLennan — his overall demeanor, his willingness and drive and focus on Maisy. It's about twice as far for us to go to Milwaukee as opposed to Iowa City. But I think it's well worth it. I mean, how do you put a price on your child’s health?”

Bringing his passion to Milwaukee

Since making the move to Children’s Wisconsin, Maisy has made the three-hour drive to see Dr. McLennan about 10 times. Most recently she was up for a catheterization in mid-July, but before that it had been more than six months since her last one. And while Dr. McLennan is still leading her care, he now has a whole team of experts working alongside him.

Since making the move to Children’s Wisconsin, Maisy has made the three-hour drive to see Dr. McLennan about 10 times. Most recently she was up for a catheterization in mid-July, but before that it had been more than six months since her last one. And while Dr. McLennan is still leading her care, he now has a whole team of experts working alongside him.

Shortly after arriving at Children’s Wisconsin, Dr. McLennan established a dedicated Pulmonary Vein Stenosis team at the Herma Heart Institute. This group — made up of Dr. McLennan, Elyan Ruiz Solano, MD, Michael Mitchell, MD, Edward Kirkpatrick, DO, Stephanie Handler, MD, and Joy Lincoln, PhD — stays on top of the latest research and meets regularly to review and discuss care for all kids at Children’s Wisconsin with PVS. Together, they come up with coordinated, thoughtful and personalized care plans for each child.

“We have six doctors who are looking at every aspect of pulmonary vein disease,” said Dr. McLennan. “Some centers might have a surgeon who knows how to do the surgery or an interventionalist who might be able to do the catheterization procedure, but here we have a team of six people with different disciplines who are dedicated to these kids. We are leading the way with research, doing studies, examining outcomes and trying to better understand and find better ways to treat this condition.”

With a condition so rare, collaboration really is the key to improving outcomes. That’s why the Herma Heart Institute joined the Pulmonary Vein Stenosis Network, an international multi-center registry that compiles clinical data on patients living with PVS. This collaboration allows the nearly 20 participating centers to share best practices and produce better outcomes. Thanks in large part to that coordinated work, and the dedication of doctors like Dr. McLennan and his colleagues in the Herma Heart Institute, the survival rates for PVS have improved dramatically.

“Twenty years ago, the five-year survival rate was about 30 percent,” said Dr. McLennan, who is also an assistant professor of pediatric cardiology at the Medical College of Wisconsin. “Today, we’ve completely flipped it, and the survival rate for PVS is 70-80 percent.”

That improvement means all the difference for Maisy. “At this point, we're just trying to buy her as much time as we can in the hopes that something else will come along,” said Tom. “Or that she gets to a point, age and size-wise, that it becomes more feasible to get her on a donor list.”

Lyndsi and Tom — and especially Maisy — have been so impressed with the care at Children’s Wisconsin they’ve actually transferred all of her care to Children’s Wisconsin — neurology, GI and nutrition.

Lyndsi and Tom — and especially Maisy — have been so impressed with the care at Children’s Wisconsin they’ve actually transferred all of her care to Children’s Wisconsin — neurology, GI and nutrition.

“I’ll take the three-hour drive for a 15 minute appointment because everyone works so well together,” said Lyndsi. “There has been no point where I felt like people weren't communicating. It makes the drive back and forth very much worth it. It’s amazing.”

Though the future remains very uncertain, right now Maisy is stable and doing well. But because of the stress and trauma she’s experienced as a result of her heart defect — coupled with strokes she suffered in December 2020 and January 2021 — she is developmentally delayed in many areas. But she continues to work and make progress, relearning how to crawl and stand and talk, forming new sounds and words every day.

Lyndsi is even looking to start Maisy in early kindergarten this fall with the help of the Children’s Wisconsin Educational Achievement Partnership Program, which collaborates between the hospital, family, community care providers and Maisy’s school to ensure she receives the right academic support to reach her optimal potential. Like so many other kids with serious health conditions, Maisy continues to be a beacon of strength, determination and resiliency.

"She is the happiest kid I've ever met in my entire life,” said Lyndsi. “She's very sassy and very determined and very independent, as much as she can be. She doesn’t care that she’s behind. She’s always smiling. She smiles from the minute she wakes up until she's too tired and goes to bed, and then starts all over again the next day.”